NOTE

While the white smoke of Munich lifted Ophelia in its open palm, while Gregor Samsa, Raskolnikov, and young Alice were singed from their pages on propagandist bonfires, while writers themselves burned dust-to-dust in Buchenwald, Auschwitz, and Terezin, Isaac Bashevis Singer was in his Upper West Side apartment learning English.

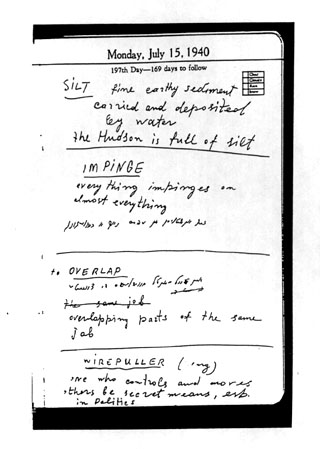

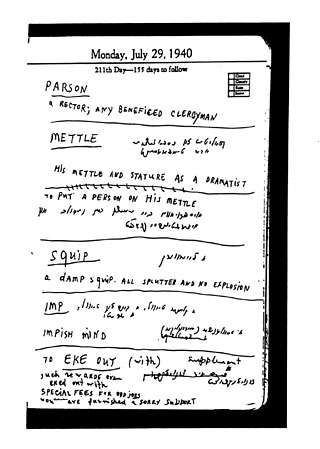

Friday, July 12: rafter. Monday, July 15: silt Wednesday, July 17: incubus, tenuous, lurid light. The days continue, three or four words each: dabble, grapple, doting, husky, wainscot, parterre, pew, appellation, fallow, aftermath, appurtenances of civilization, the mutability of the quality we call American, erosion, lucid …

These eighteen days—shown here for the first time, courtesy of the Judaic Collection of the Florida State University Libraries—represent the longest continuous span of such vocabulary-building in Singer’s daily journal for 1940, the year he began his first writings in English. Other pages contain doodles, reminders, scribbled plot seeds for stories and novels never planted, and seemingly random notes, including a kind of daily credo, which includes:

Whatever I have to do today, no matter how annoying my work, how irritating or futile my task is, I am going to accomplish it in the best possible way, in a manner as if the whole world and its future would depend on it.

—a sentiment at once adolescent and prophetic.

These pages of Singer’s are not great literature; surely they were never intended to be published. But like all great literature, like the stories, plays, and poems by which these eighteen days are now surrounded, they are the product of a seemingly impossible faith in communication—of person to person, idea to utterance, mind to hand to paper—a faith made so much more impossible in the new era of Babel in which Singer was learning English.

Judaism is a religion of words. While Yiddish was the language of the shtetl, and almost all of Singer’s writing, it is Hebrew that rests on Judaism. The Hebrew language contains far fewer words than English does, most words have several meanings, and all words have profound and profoundly unavoidable biblical resonances. Words are sacred, and inextricably linked with other words, as well as numbers and subcutaneous meaning. One could not, for example, think of eighteen days without at once noting that eighteen is the numerical equivalent to chai, Hebrew for “life.” Here, against a backdrop of broken glass and human incineration, is a chapter of life. A quiet chapter, yes. A chapter easily lost in the dark corners of Jewish history. But an essential chapter: while Torahs were made into lampshades, while scholars were made into lampshades, Singer was learning words.

In the beginning was the word …

Honor the word …

Etch the word on the doorposts of your house and on your gates …

Yes, but what word? What word?

Singer’s most loved myth (which became the subiect of his most brilliant fiction) was that of the Golem, a monster made of clay and soil by Prague’s chief rabbi, to save the Jews from persecution. To give the beast life, the rabbi placed a slip of parchment under its tongue, on which was written the unknowable, unspeakable name of God.

Singer too held this under his tongue; he saw his task as a kind of modern version of the Golem’s. But it was not only the God under his tongue that he had faith in. It was the word: the unknowable word for which we search, for which we exhaust dictionaries, for which we write and erase and write again, the word whose existence we believe in without any proof, the next word we will learn, which we pray will come closer to expressing our desired meaning. Our God of the lexicon. A God we can believe in.