In November I returned to Salt Lake City after thirty-four years and while lost on one of those streets with no name ran into a childhood friend I almost didn’t recognize because we’d both grown fat and wrinkled like widows in a Renaissance painting, and after an hour of idle chitchat we retired to a hotel lobby where my friend shared the news that Yelena Zubredevya, the singularly odd Sunday-school chorister, had walked out onto the glacier the night before and not returned, one week after her eighty-first birthday. I refused to believe it. Even after reviewing the bread crumbs of her life in the newspaper obituary, and even after my friend leaned close and confessed all these years she still heard Miss Z’s voice in her ear, a voice that the doctor dismissed as mere tinnitus, and didn’t I still hear voices too?—even then I doubted it was possible for Miss Z to be gone, for the presence of the glacier was proof that nothing was ever truly gone anymore, only displaced, like moving from one room to the next, and the more I tried to forget her the more my head began to swim with thoughts of Miss Z.

She lived on M street in the Avenues, number 116, a house Brigham Young built for his favorite wife, who went mad a century earlier. Miss Z was not religious but she liked to tell people this inconsequential detail as she believed it lent her an aura of mystique and endeared her to the local Mormons, who found her eccentric. By the time we knew her, the once-flamboyant Queen Anne home was falling apart: the wood rotted, the roof a parliament for fungus, the windows soap scummed, and the yard a refuge for monstrous blooms of peppermint, which Miss Z boiled and baked into candies. All the neighborhood children took piano lessons from her. The sticky fingers and icy peppermint throat were the hard-earned reward for enduring half an hour under her strict tutelage as she disciplined our fingers to know a note after a note after a note could form something that was greater and more meaningful than the individual sounds.

Her methods were unconventional. God may speak English, she used to say, but music knows only Italian. Before touching the piano, she required a rudimentary knowledge of the language. For a time, the playground was abuzz with phrases like Sputa il rospo! and In bocca al lupo! She took all her pupils—even the frightened ones like me—to the Utah State asylum to converse with an elderly Italian gentleman who talked for more than an hour about his native homeland, by that time submerged in the Mediterranean by rising sea levels. Wild stories, no doubt, based on his facial expressions, but completely incomprehensible, and it all must have been too much for him because one afternoon Miss Z said he’d drowned himself in the bathtub. She never raised her voice above a whisper, sitting on the piano bench with eyes closed, mildly catatonic, tapping the beat with her fingers, moving slowly and with great difficulty because of one withered leg covered in milky scars, the result of a childhood illness or accident we never knew. Halfway through a lesson her eyes would suddenly fling open and she would dole out peppermints and regale us with stories of composers. Hildegard von Bingen, who wore a girdle of thorns to summon angelic choirs. Mozart, who penned lullabies to his cousin about shitting on her face. Clara Schumann, whose talents far surpassed those of her more famous husband. And our favorite, poor Joseph Haydn’s head, decapitated and robbed from his grave and kept in the bed of a Viennese opera singer who hoped to divine its musical genius.

Even though I enjoyed these macabre stories more than playing the piano itself, I knew they were prelude to a trip to the glacier at the end of each lesson, where we stood at the ice front listening to the groans and gasps of deforming ice, a soundtrack that left me with the anxiety that to exist in this world things must be either very large or very small and anything in between would surely disappear. Miss Z encouraged me to get uncomfortably close to it, put my hands on it even, something my superstitious parents warned me never to do. They had heard rumors. How early in the epidemic at a recital in Miss Z’s house, a student, a snot-faced boy who teased everyone at school, suddenly crumpled into ice mid performance. Miss Z, supposedly, walked slowly from the back of the room. She swept up what was left of the ice boy into a bucket and finished his performance—Chopin’s Fantaisie-Impromptu op. 66, I think—without batting an eye. She was the only one in the valley we knew whose body was untouched by glacier. Not even a little patch like the rest of us eventually had on our knees and elbows. As if the glacier were afraid of, maybe even mesmerized by, her.

I never asked if the rumors were true. When the sky grew dark she walked me home in silence.

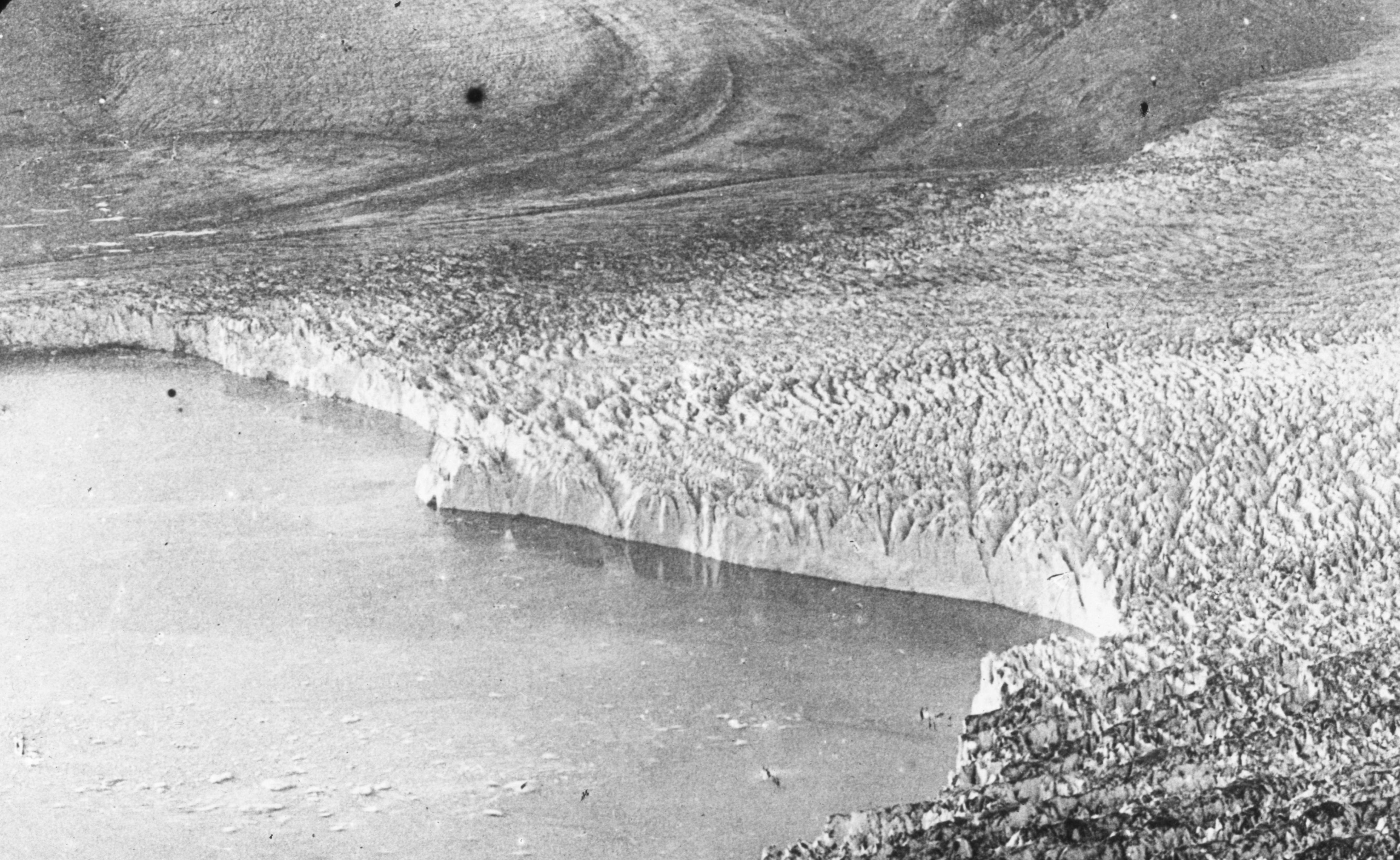

I remained at the deserted hotel as long as I could. Spying the glacier from a distance it was obvious that after enduring the sun all day it preferred the moon, soaking up its glow as if they were lovers. Too anxious to visit my childhood neighborhood, I wandered the streets aimlessly, finding empty doorways and abandoned bicycles, the echoes of cane baby, cane baby, cane baby still rattling around my head, that old nickname because I was never without one of Miss Z’s candy canes hanging from my lip, then crossing the railroad tracks past the slaughterhouse and glassworks and fabric warehouses, all strangely silent, only the fertilizer plant coughing yellow smoke from its chimneys, suddenly overcome with a longing for nightfall until remembering night hardly existed here anymore owing to the glacier, whose soft whiteness illuminated the desert and inspired a city of insomniacs of whom I was the most recent convert. As I walked, I recalled the early days of the glacier, its slow advancement from uneven patches of ice confusing scientists until becoming a fat, white tongue thickening in the dried-out lake bed, and how for so long we had resigned ourselves to the emptiness that comes with extinction, no longer hopeful of rewilding, no longer sunbeams in Sunday school singing praises but chanting under our breaths Jesus wants me for a catastrophe that we surrendered to the glacier’s demands willingly and without question. If Miss Z had indeed walked out into the glacier it was nothing exceptional. Every day of my childhood men and women wandered silently into its emptiness. And the glacier grew whiter and thicker.

When, in the nature of things, there were no more children for piano lessons, Miss Z opened a kiosk near Stansbury Bay, the eastern edge of the glacier that was often slightly pinkish from algae blooms, where she sold bouquets of bright plastic flowers. Sometimes a feral cat wandered by, ignoring her efforts to entice it with peppermint candies. Otherwise, she was alone. Little by little, her reputation was almost equal to that of the glacier. Many despised her and found her diligent caretaking, what they called her affection, unnatural. Others loved her and made it a point to visit her kiosk. As is the nature of things, her strangeness was soon ignored and forgotten. In the evenings she chiseled away a bucket of glacier ice for boiling confectioners’-sugar water and could be seen limping up the steep hill back home. Nobody offered to help.

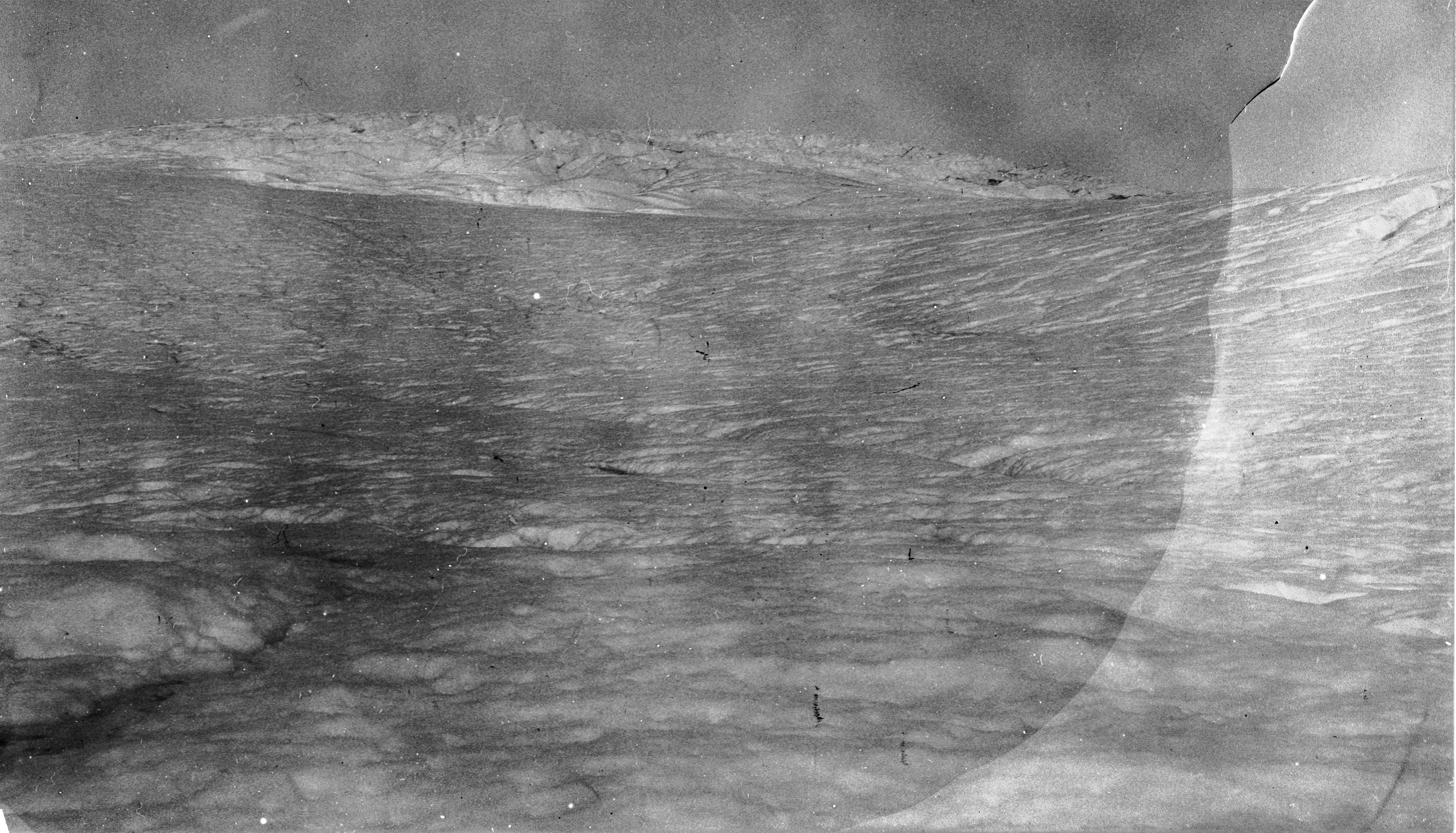

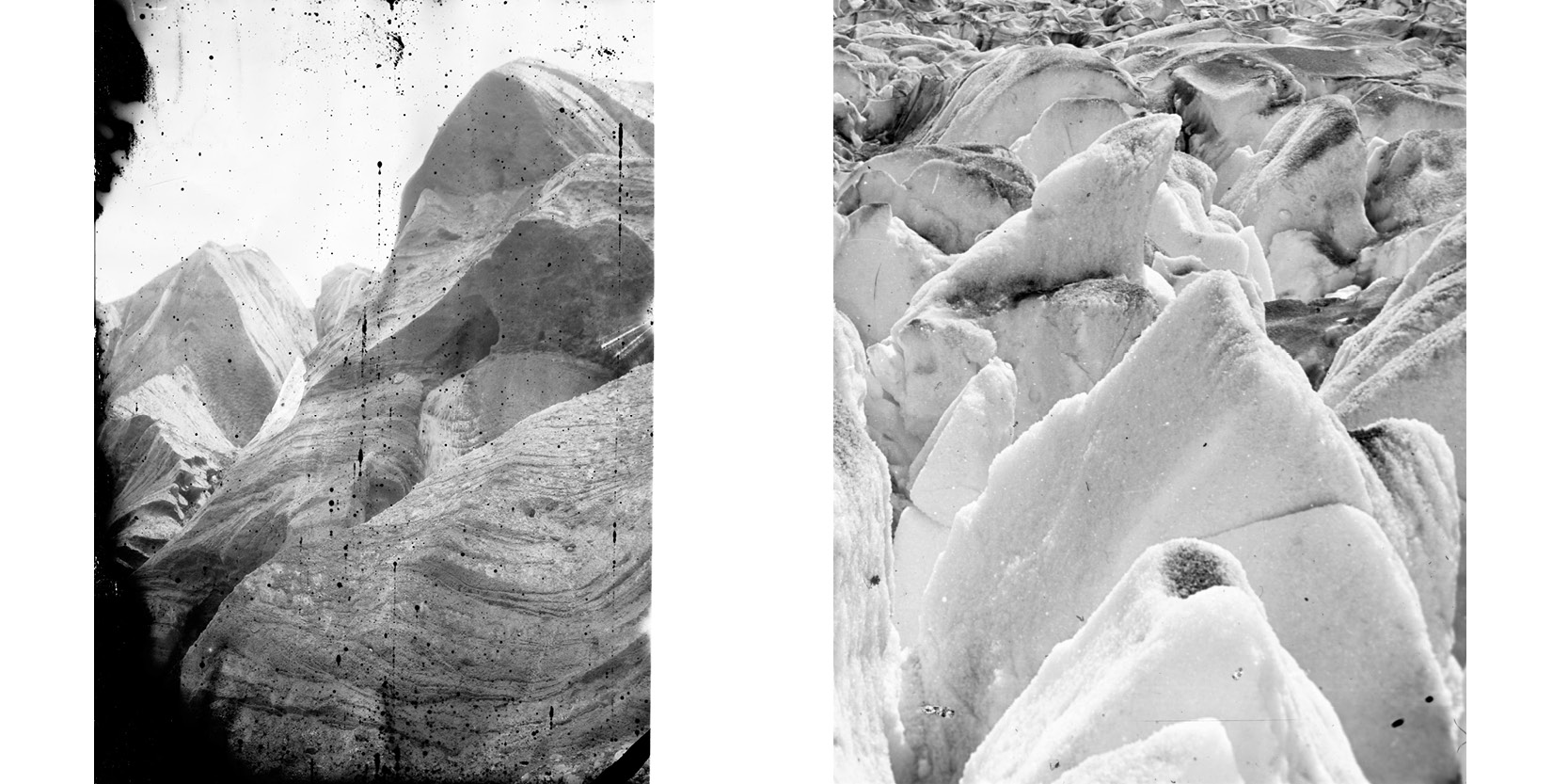

It had been years since I’d seen the glacier up close. It was far bigger than I remembered: a vast, monstrous whiteness. My mind balked at the size of it, distressed how the earth could imagine something so alien. Most people seeing the glacier up close for the first time are stunned. Utah is so far west, so unreal, it feels dangling off the map. And the desert. So much desert. If visitors remember history lessons from middle school, it’s only antique photos of the old Salt Lake. Pioneers floating like pickles. Of course, they remember the news bulletins of the megadrought and vanishing lake, reporters covered in arsenic dust with the unapologetic sun leaving an empty dust bowl in the background. But people now have a hard time looking at the glacier with its weird, unnerving beauty. Like it doesn’t belong here. Like it isn’t really a glacier because a glacier must have a hidden flow and move beneath the weight of its own unbearable mass, becoming what one polar explorer called a faint dreamy color music, a faraway, long-drawn-out melody on muted strings. And yet it’s always there, the glacier, whether you believed it or not, just there, a savage, ominous thereness.

I kept my distance, perched on the nearby rocks like a gull, waiting for someone to tell me what I came for. The kiosk was disheveled as if Miss Z expected to return. I tried to picture her on the wobbly stool, mildly catatonic as the halogen bulb attracted moths, and her gnarled and calloused fingers glued together plastic flowers. I tried to imagine her walking out into that strange whiteness, her body dwarfed until slowly dissolving like a grain of sugar on a tongue. Most women her age had at least a few visible icy patches, their wrinkles scarred over from tiny seizures of joy that crystallized and chafed the skin, but I imagined she was soft and smooth, her body slender like an eel. I rummaged through boxes, hoping I’d find some memento of her, perhaps even the sculpture I’d made, a glass Chopin death mask, the only gift I’d ever given anyone assembled from jagged bits and pieces stolen from the glassworks and windows shattered around town. I left it on her doorstep on the anniversary of the composer’s birthday thinking at my next lesson she would put it on display near the piano, but I never saw it again, and in shame I had stumbled over the notes so badly she put her hands over mine, my face flushed wild red. It was the one time I felt she’d thought of me as more alive than the glacier. She would sometimes spend entire lessons telling me about the crystalline structure of ice, millions of microscopic crystals stacked on top of each other, pressing and sighing in a sea of frozen lattices, the ice layering on ice exponentially, like skin, and even if she believed she could escape it, which she did not, she knew she could never escape it, that even brief day trips away from the city upset her and that the glacier had left an invisible mark on her. It had, I remember her saying, taken possession of her, crowding out her memories until there was nothing of her left.

I thumbed through an old photograph bin. As best I could tell, Miss Z had been taking pictures off and on for years using an old tripod camera that was collecting dust in the corner, developing the negatives in a closet or bathtub with harsh chemicals that probably turned her hair white, slowly, because everything is slow now. Most were blurry, the images grainy and warped with double exposure, but the glacier always loomed like a cabaret dancer. Her photographic obsession started as a kind of romance, I told myself, like she was trying to capture a lover unawares, but a lover that disgusted her, only to find herself surrendering to the fascination of disgust. I was glad I wasn’t here to see her like this. It is a difficult thing to watch someone love something that doesn’t love them back. Eventually, she turned the photos into postcards that she mailed indiscriminately all over the world with the same cryptic message scribbled on the back: Dirlo al ghiacco. Go tell it to the ice.

One of the postcards ended up in the hands of some Czech tourists in whose company I found myself after circling the streets until sunrise. They’d come for the glacier. But whether to witness it or become part of it I couldn’t tell. We made loops around the city. Wandering up the canyon before surveying Temple Square, where one of them, a pathologically shy puppeteer who called himself Švankmajer, hurried away like a bespectacled hippopotamus from all the Mormons trying to shake his hands and convert him. Later, we retired to the Lion House, where Švankmajer ordered a meal of frontier delicacies befitting a polygamist commune. While he silently ate roll after roll slathered in honey butter, those in his entourage discussed the glacier, several of them inviting locals from nearby tables to examine the icy wounds on their bodies: dendrites growing out of their necks, noses covered in snowflake-like fractals, and even one child whose teeth were entirely ice. I did my best to explain the glacier to the incredulous Czechs. It was ice, but it was something else too: the swirls of turquoise and hypnotic flatness, meltwater ponds and hoarfrost that advanced year after year despite the fact that snow didn’t fall anymore—the glacier was human, the ice the residue of bodies that had, in the nature of things, crumbled away from joy. Little moments of happiness and pleasure didn’t do much to the bodies out here. Maybe a numbing tingle in the fingertips or a patch of frost on your knee. It was joy you had to worry about. The deep, stabbing bliss. Joy was what caused husbands to wake up and find husbands a heap of ice, or mothers at the playground suddenly itchy, then brittle, then icicles in the sandbox, nature evening things out, taking back something from those who had stolen so much.

Marriages were rare. Births almost nonexistent. People feared the human in them. They fashioned reserves of guilt, shame, and indifference as a buffer against the glacier’s appetite. But joy is a fickle thing. Sometimes it happened all at once, the body dissolving into a fine, snowy powder, and other times slowly flaking away. Naturally, scientists were encouraged by the glacier’s expansion. We might be able to reverse our climate catastrophes, they said with the monotone optimism of a snail, but only if we continue to feed it our joy. How much were we willing to sacrifice for catastrophe?

My voice was soft and dreamy. Švankmajer rubbed his bald head as if it were a peeled egg before dismissing me with a wave of his hand. Only puppets are magical, he said.

It was late when we finally made it to the glacier. It was not crowded. A naked woman sat in a lotus pose a few hundred feet from the shoreline, her icy shoulders in the first stages of melting. A couple spread a bucket of ice into a thin layer. They stood quietly then walked away.

The Czechs stood in a puzzled awe. They murmured. They did not blink. It was obvious they wanted to touch the glacier. They likely had never seen ice before, what with the scarcity—indeed, the rarity—of fresh water across the globe. The Dead Sea was a salt flat. The dusty Nile Highway. The Amazon a trough. Sand dunes spread over what was once Lake Victoria seemed like withered nipples. From outer space, the Ganges, home to a cemetery of old boats, looked like a frayed jump rope.

Leaning close to me, Švankmajer asked if it was painful. Becoming glacier. Is it painful?

I shrugged. Just walk, I told him as Miss Z told everyone, and the glacier will do the rest.

Švankmajer paced the shoreline for more than an hour, plucking his beard like an illegitimate Merovingian. I’m sorry, he finally said, arms dangling like dead fish, I just don’t believe it.

That’s the unfortunate thing about Utah, I said with a hint of disenchantment, nobody believes anything.

Švankmajer wandered off to the nearby meltwater pond. For the next several hours he knelt in the brackish water and filmed flies and sketched storyboards on napkins as a new puppet film took shape in his mind. A year from now this will be gone, he said, waving his hand at the glacier. Reality is a tissue of dreams but puppets, he smiled, puppets last forever.

Before leaving, the Czechs looked for their companion who had been lying on the glacier giggling. They found what seemed like the impression of a deformed angel in the ice. They called his name. The sun went down. They quit trying.

I sat on the wobbly kiosk stool until a woman tapped on the window. Is this your shop? she asked. She was pregnant. Her lips were blue and in place of eyebrows grew jagged crystals.

Yes, I lied, my mind snapping like a rubber band out of its reverie.

My husband, she said in a faraway voice as she hoisted a bucket of ice. The world is sick.

She cupped a handful of the husband ice. Traced a finger over the slick edges, pausing as if trying to imagine it was still him. This sliver here not unlike his eye. This dimple here might have been the congenital defect in his heart. This jagged crust like the time he broke a tooth eating popcorn at the movies. I thought of telling her that as ice melts it tessellates. That if you look closely it forms an almost incomprehensible web of spikes, cones, pyramids, kites, stars, spindles. Nature, like an infirmed fairy tale, has so many shapes.

When she tired of her mental resurrecting she spilled the handful of ice back into the bucket. It crackled. Like he was still talking, speaking in a language none of us understood.

My grandfather had cancer, she said abruptly. He was one of the last. Natural causes. She almost laughed saying it. She found him sitting at his desk, pistol still in his fingers, a small black hole above his temple dripping blood.

Goddamn, I’d give anything for that, she said. Anything except this dead not dead.

Yes, I said dreamily, trying not to listen, trying not to imagine with her. I stared at the bucket of ice dripping water, the drips swallowed up by the desert dust. I stared past her into the glacial whiteness.

NOTE. All photos courtesy of the Ralph Stockman Tarr collection, “Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland,” at Cornell University Library.

This story appears in our spring 2023 issue, Conjunctions:80, Ways of Water.