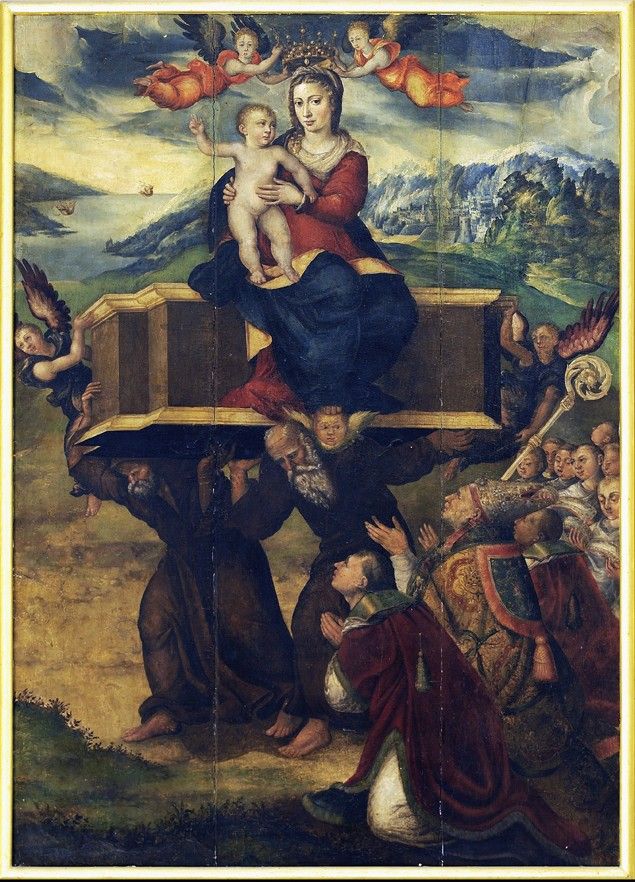

Madonna dell’Itria, 1579, Sofonisba Anguissola

The Way

If only the waters were still this blue,

the boats this innocent. The sea,

the clouds, the cliff faces: blue, blue, blue.

And me in a red dress with a blue mantle

draped over my lap to keep my legs warm.

It’s true, I’m sitting on a coffin

with the lid down. The lid

is called a crown. The coffin is filled

with what happens when evil takes over

the world and says yes to giving

the lost unlimited hate

and all the weapons they want. You’ll say,

“That wasn’t my fault, I’m like you, Mary,

I was only ever being fabric

and two hands, harmless arms and a mind

filled with maxims—only ever on my way

to tomorrow, my right foot at rest

on the head of a cherub.” Do you hear

the ticking behind the sunrise and see

that someone’s added mud to the milk

of religion? If so, you truly are like me.

And you know it’s not wise to worship

at the altar of the selfie. You know free will

means free will. You never ever play God.

Here in the ether, the world that weighs.

Madonna of Mercy, Domenico Ghirlandaio, c. 1472, fresco

Mary, Bible Character, Hand Puppet

A polished plate on my head

and on my feet, the pink booties

that remind me of childhood,

and a big-tent capacious drape

that acts like a cape to keep me warm

and draw people in. I show them

all mercy but they don’t show it back.

This appears to be a religion

that takes what it wants

and messes with the rest.

You can’t have me and leave out

the story of the eye of a needle.

The leper and the sex-worker.

Who’s looking at whom? Who’s being

a human? Who’s playing the angel?

My son hated hypocrites so

wouldn’t like to see you telling others

what to do. You could say

each image of me was designed

by a demon to be a multipurpose

machine to generate empathy

for some but not others.

You’ve made me an inflatable doll

to do with whatever you want.

Unmerciful world. Bitter enviers.

Annunciation, Leonardo da Vinci, 1472

Mary and Silence

Hush and quiet and shhh. It’s all the same.

Someday we die. It’s true and it’s only the way

things will be. You can call it God,

you can call it fate. You can say whatever you like.

My son was and that’s a fact.

And after the fact, there’s this: It’s fine to live

for a day. It’s fine not to live at all.

Be selective about what you believe. Try

to be humble. Stop thinking you know more

than you do. You have to stop tyrants.

You have to stop hating. Stop in the name of.

Not seeing harm will not excuse you.

The angel’s wings are based on a bird of prey.

There’s also a shadow in the grass which is proof

that an angel has a body

that blocks the light as much as the trees

in the background. As much as pretending

the impossible took place. The truth is

a metaphor is a way of imagining the world.

The real world is fact and act, tempered

by the overwhelming quiet of before and after

the high-pitched confusion of a dole of doves.

A group of turtle doves is called

a pitying, a pity is when your life is sitting

next to you in algor mortis, the cold hold

of death. That inconsistency is the single subject

of the conversation you and the angel are having

Enthroned Virgin and Child, 12th century; French; wood with traces of paint

Wisdom

Someone has lost their head. It happens.

The body is fragile. The mind even more so.

The sun rose today as it has done

for centuries, as it once did when we were

on the savannah and only beginning

to be. By we, I mean that odd iteration

of animal intelligence we call ourselves.

And yet look at us, slaughtering each other

the way watching the lions do

to each other taught us to slaughter:

mindlessly, selfishly, as if in that moment,

there is no one else on the planet.

As if there is nothing better to do. No cave

walls worth painting, no solar eclipse

worth waiting for. A lion will kill a lion

to establish territory, or if it’s starving.

We aren’t starving when we kill one another.

We kill what is fragile and damaged

and no longer the ideal it once was.

We say goodbye and leave our sad faces

to stare out of a bank as blank as wood

worn down by time, elements, boring insects,

and attempts at repair that went nowhere.

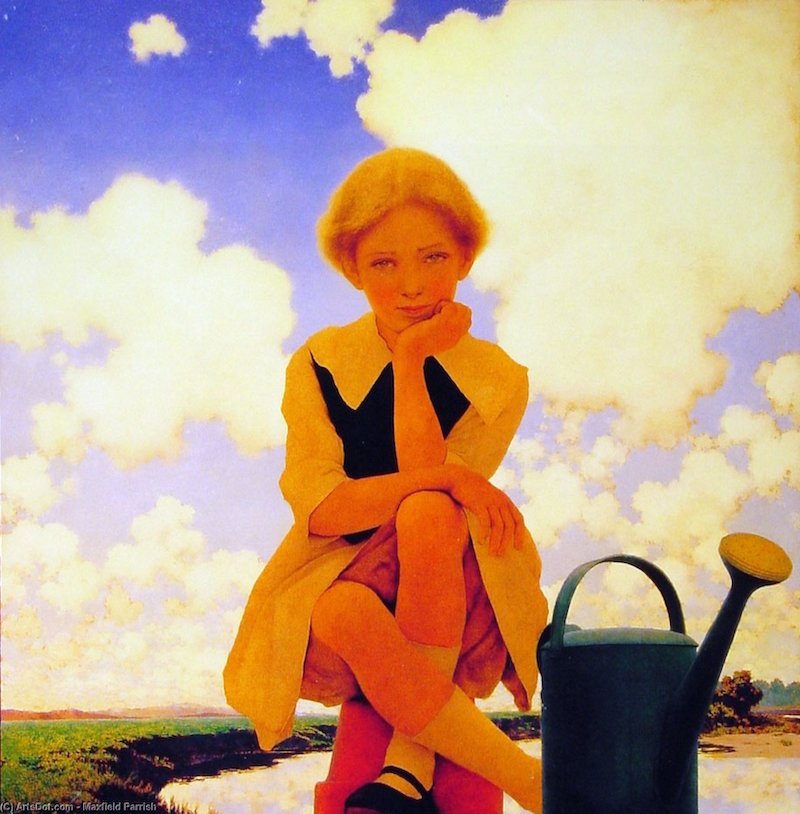

Mary, Mary Quite Contrary, Maxfield Parrish, 1921

Mistress Mary, Quite

Contrary equals: as in realism, also in artifice.

Both act like the diamond-point engraving

done by air, wind and water in the interest

of accuracy. In the interest of demonstrating

technique to the diamond trade between earth

and the sky where the stars are.

Where the moon is. Where a porcelain nun

behind a wrought-iron gate says, “You can’t

begin to understand,” to a visitor in a hat

who asks, “What’s it like in there?” This Mary

that wears gloves, and dresses in dresses,

is sister to the one that is asleep on the job

of resisting the sweep of time that refuses

to let go of what came before. “Mary, Mary,”

someone says. Mary thinks it’s her mother

but how can that be when her mother left earth

such a long time ago? She still thinks of her.

She’s not that contrary, she has a subjectivity.

Madonna of the Book, Sandro Botticelli, ca. 1480–1482

Madonna of the Book

Madonna of the book, of the basket of fruit.

Or flowers. In a bowl. Or a basket.

Madonna of the sky outside. Madonna.

My Lady. My glass-bead neckline Madonna

of the book in the language that says

how to raise horses, raise bees, plant land,

grow trees. A Virgilian offering

for the Madonna of earthlings on earth

where late-night arrives in blue velvet.

Where everyone wants to be more

than a bent head. In The Hours and Days

Made from Them, there are countless bees

crawling on a gigantic balloon made of bees

floating in an aqua sea

that’s drifting, looking for the water of Lethe.

The Coronation of the Virgin, Annibale Carracci, after 1595

Mary, Queen of the Universe

Which universe isn’t important, it’s being

that matters. Scepter, crown,

tasteful tiara at the tea table or at any event

that deserves less respect than a full-blown

coronation. All eyes are on her

comportment. Is it queen-suitable?

Yes, no, maybe she hasn’t heard

the tittering muffled by the fans

of the courtesans lounging in the hall

to the right of the room in the palace behind

the famous façade—where she tells

her secrets to no one. Where a dog growls

at the footman who brushed it aside

while her royal eyes were reading decrees,

written by others, yes, but clearly signed

by her. She’s only a signifier but signifiers eat,

drink, and act merry from time to time.

Acting is what we do, unless we don’t,

and then refusal leads to anarchy and who

would want that? No queen ever would

not act. Unless, she was asleep.

Then she’d be like you and me, dreaming

of being unaware of the audience watching

the play called The Queen of Being Seen.