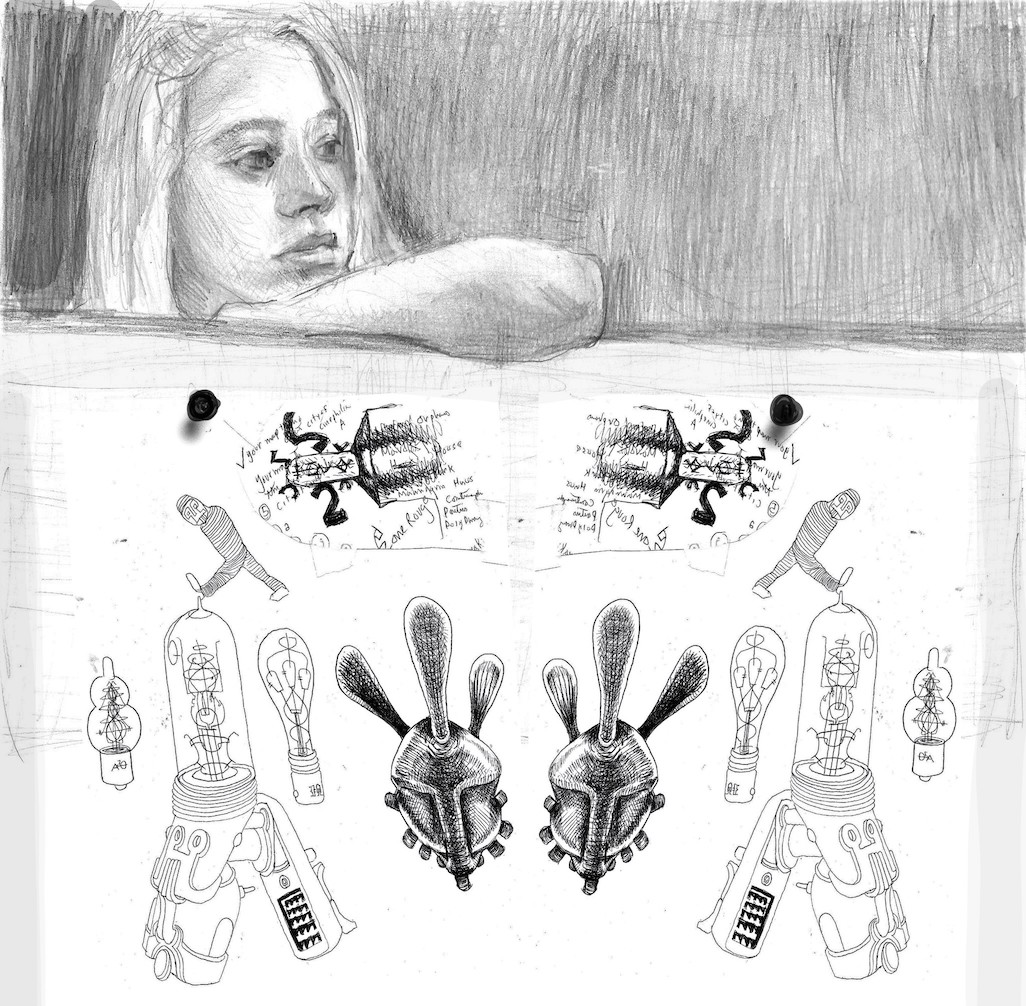

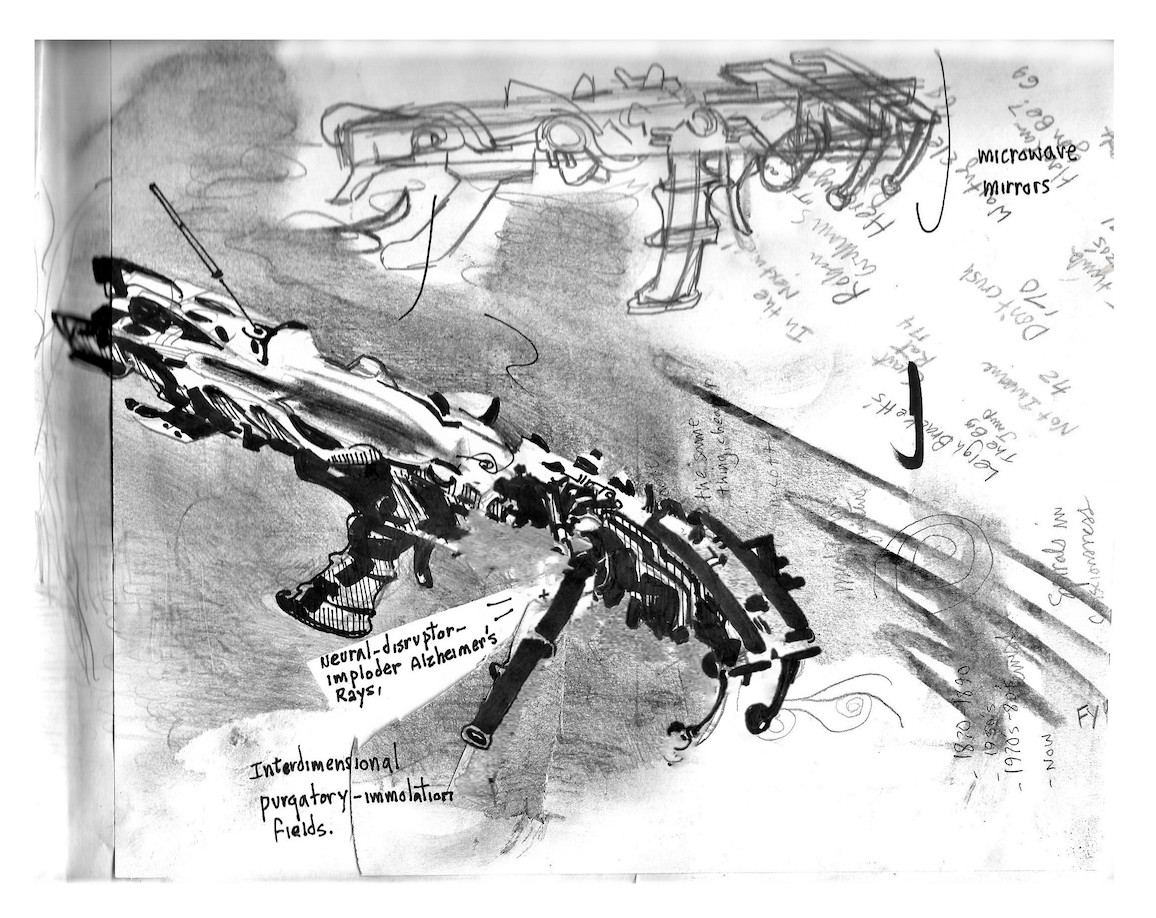

I called my machine a fugue gun.

That night Bonanza rolled and buzzed. My dad scrambled for a cure in twitching dials, thumping fists, a waving of antennae in witchdoctors’ gyre over everyone’s head. I snuck away to my room. It only took a minute before he knew who to blame. The doorknob twisted and shook and there were pounds and kicks. My father shouted to come out this instant, his voice stabbing into the red. The zone rouge of war wound and rage. I jammed the purloined antenna into the plug and threw the switch. My machine strummed the superstrings. A future was Now: Ben, Hoss, Little Joe, Adam, my dad and my mom were long dead, and my son along with them. I was sitting in my grown-up office, watching a dying stinkbug on my grown-up office windowsill. From far off I heard a “Hey.” Billie my colleague was peering over the partition wall between our cubicles.

“Tom? What’s wrong with Jeremy?” She gave all the office stinkbugs the collective name Jeremy.

“I think she’s had it.”

“Jeremy’s a she?”

“I think this one is.”

“Huh.”

We stopped breathing. Jeremy’s bent antenna gave a goodbye salute. I let out a breath and Billie said “Crap,” lingering a little with her head doing that humpy-dumpty totter on the cubby wall between silence and something else, sometimes a question about nothing much, sometimes a little less of nothing into something I couldn’t get: What’s going on? What’s doing? Trying to answer, I always drew a blank. In my head. On a sheet of paper. Or with a flash behind my eyes, a buzzing retinal fatigue of the brain. I’d learned to smile it away. Talk bugs.

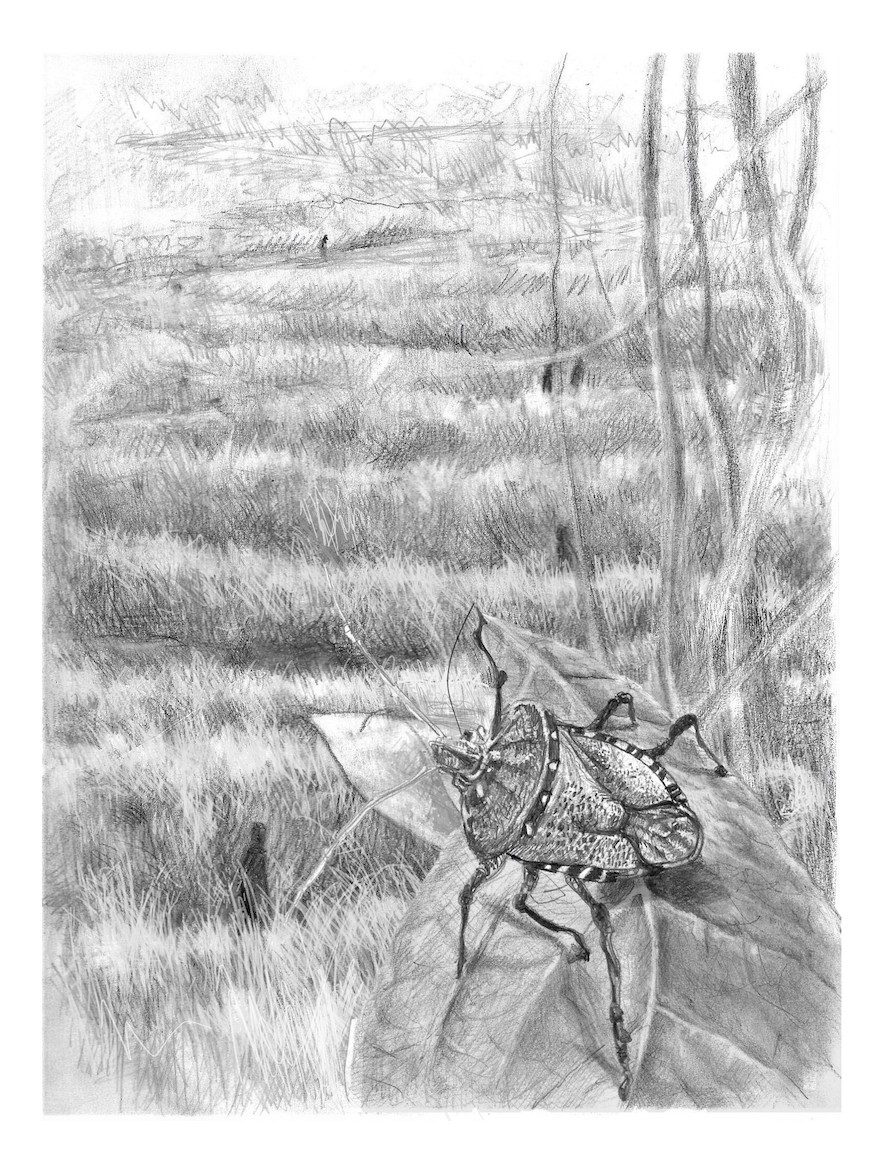

I’d been creating some lesson plans about insects for my advanced ESL class. Sort of. I sketched the failing Jeremy and googled more about stinkbugs. I’d already learned Jeremy belongs to the Pentatomidae super family of bugs, for its five-sectioned antennae, where a lot of its brains are located. It’s also known as a stink bug for its defensive odor, likened to coriander, cilantro, or skunk. Since the only way I had ever learned was to teach, my days were spent stringing beads of teaching moments from stuff around me, at the moment bugs, and consciousness. Lately the thread had broken, the moments and beads spilling out on the floor. Life was tidying up, wasn’t it. Maybe this was a juncture moment, why my machine had delivered me to this now. Maybe the answer to why I kept going blank with Billie, with everything.

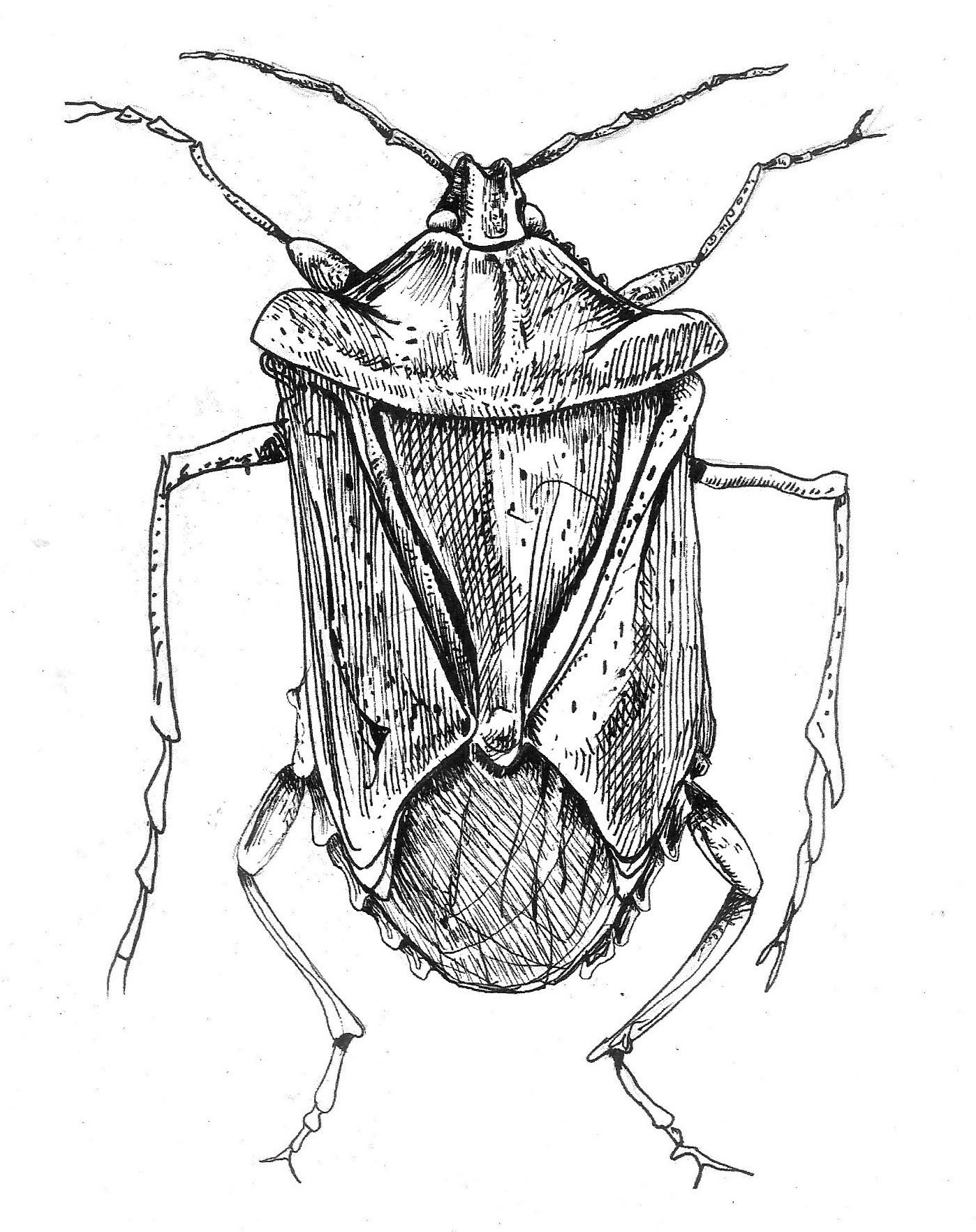

But for the moment I read on. Stinkbugs are classed as “Shield Bugs.” They have an escutcheon shape, like a coat of arms, in Jeremy’s case resembling some nomadic tribal armor made of brown cured skins stretched over cages of bone and branch. The leathery brinded shield is called a scutellum. Below a bump two thirds down it opens, theater-curtain style. Filling out the bottom half of the shield are near invisible translucent brown wings tucked one atop another. They’re edged with a dun and black triangular checkerboard band of wing membrane peeking out, like the hem of an A-Line skirt caught in a shut car door. Across the top of the shield is a gray banner with five black spots. Males have bumpy spots, and females smooth. Jeremy’s seem smooth. Above is a little brown nub of a head housing two tiny ocelli (simple eyes) and a pair of larger, compound eyes goggling out the sides. After a time I fell down other various rabbit holes of google, and strange.

Put down your weapon.

Where had I just been? A day fever-dream.

“Hey Tom?”

It was Billie on the other side of the wall.

“Yeah?”

“I just read that the last of the Wisconsin ‘Wonder Spots’ has closed.” They were highway tourist traps big in the 1950’s and 1960’s that claimed to be among a few dozen power points on the Earth. The roadside signs read, ‘Where the laws of gravity have been repealed!’ Visitors standing upright looked tilted. Milk came out of cartons at a slant. A chair could balance on one leg.

“Huh.”

She e-mailed postcards, articles and billboard pictures online and said, “More realia for a lesson.”

“Thanks.”

“I wish they were still open.” Then we went back to work.

Composition Question: Do you believe the Wonder Spot was real? What is happening in these pictures? What could it mean to “repeal the laws of gravity”?

There was something hot in the air.

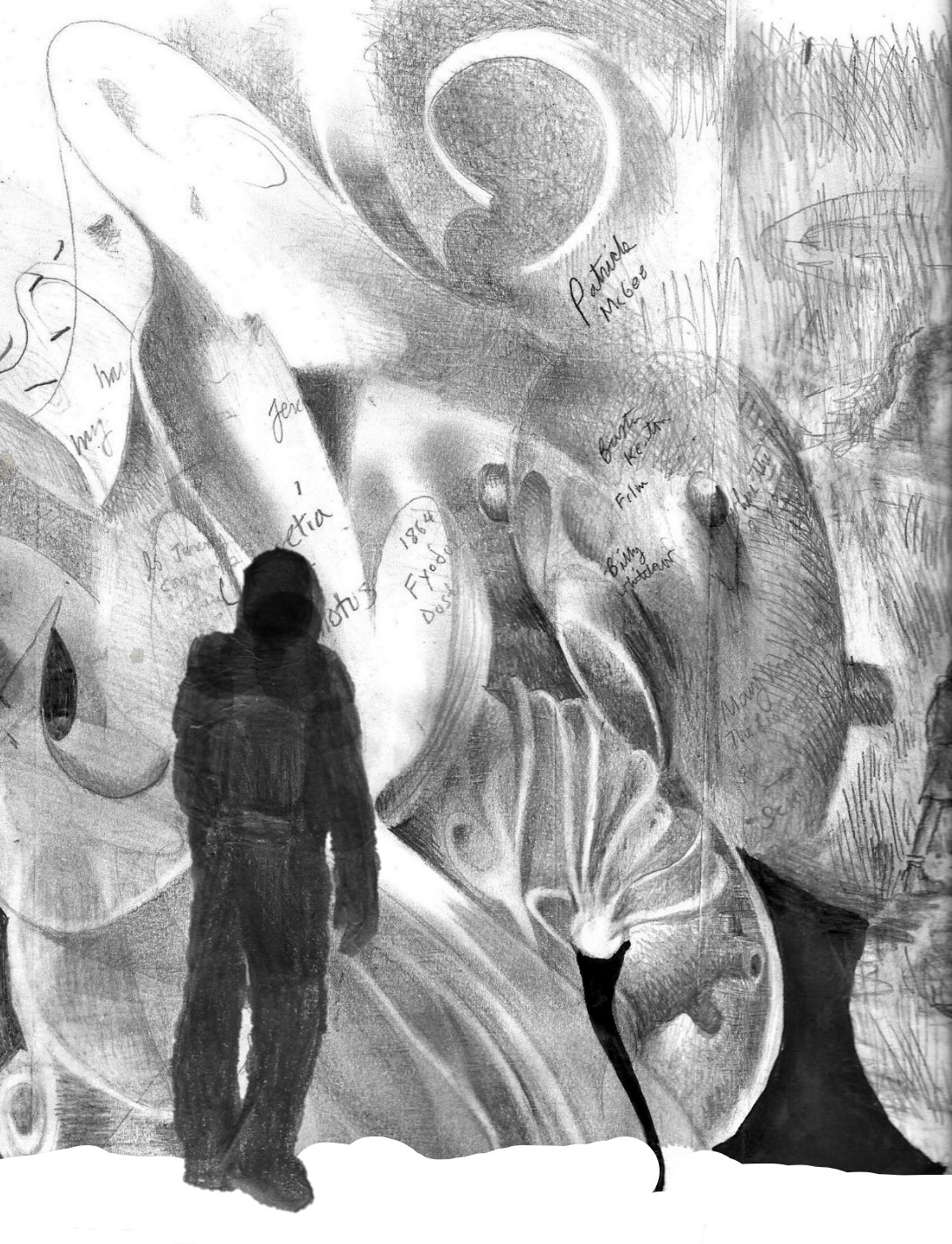

Put down your weapon!

I remembered a graphic novel I had just read by the Belgian-French team of Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters, The Leaning Girl. I wanted to tell Billie but decided to leave her alone. The Leaning Girl told of a young woman, Mary Von Rathen, who could only stand at an acute angle. Her gravity-defying condition proved to be an opening into another dimension. The storytelling and drawing beautifully visualized an elegant, Jules Verne/steam-punk world of “The Obscure Cities.” Maybe I could use a little of that. A memory of envy and longing flitted by and was gone. I used to be hungry. Ambitions to build my own alternate worlds filled sketchbooks. But let’s stay moored to facts, and the quotidian. Now my drawings doodle across my classroom handouts and whiteboards, like a leak in the pipes that I must get fixed. Fix things. Batten hatches. Katy bar the door. Attach that fourth leg to the chair. My son could float and lean and hang like that. Defy gravity. Of course, he loved free climbing. There was some kind of accident. But back to the bug lesson:

The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, Pentatomoidea Halyomorpha halys, is native to China and Japan, a stowaway to North America on some packing crate or farm machinery sometime around 1998. Halyomorpa halys is an infestation, feeding on fruit and vegetable crops with a piercing, acid-spewing mouth inflicting “corky wounds.” A gnarling distortion results, called “catface” (so named because the surrounding healthy plant growth bulges around the poisoned hole like the puffy cheeks of a cat). Jeremy never uses his stabber on people, though one article warns of “irritation from the scraping edge of the wing membranes.”

The smell of overheated electronics. Something about to blow.

Put down your weapon!

Jeremy always accepted my outstretched finger for a trusting walk up my palm, a pilgrim with cat’s feet and doubt. This was not a self-portrait, but it would have been nice, I think, if it were, if this creature of a me lived a modest, gentle, beautiful and discrete lifetime on this earth, the very essence of a light footprint life, doing no harm and maybe a little good within a little realm about as big as my cubicle.

But outside this benign office is a predator. An invader. A blight on crops and households, poking and sucking out Corky Wounds and Cat Face disfigurements with the piquant calling card of cilantro, the penetrating tear gas of skunk. My national superfamily reeks of the colonialist and fascist, the biggest arms dealer in the world and one of the biggest polluters and resource gobblers, tear gassing asylum-seeking families at our border, putting children in cages and wrapping them in silver blankets, butchering families with drones, following the orders of the alpha bug.

When Jeremy takes flight, it is with a drone’s leisure, and I wondered when Amazon delivery drones would become as commonplace as stinkbugs. There would be an enthusiasm for shooting the drones down, I hoped. I dreamed.

I looked up and it was just there again, Jeremy, sitting on my tabletop or keyboard, peering over my cubby partitions, or trudging across the broad window sill or clinging to the glass between inner and outer panes. Jeremy had come to the office not to feed or lay eggs, but to stay warm. And to die.

I knew my research into bugs was a distraction, and a salve. My online clicks and scrolls were a digital descendent of my parents’ anxious coaxing of dials and antennae for a clear, true picture.

Something was definitely burning.

Billie had just said again, “Hey, if you want to talk…”

I said, “About what?” I wanted to be smiling.

She was a little jittery. A jittery I noticed more and more. Was it that funny fusion of shrug and head shake, bunched-up smile, squeezed or bug eyes mid-western nice thing that conveyed a very mild gumbo of concern? About what? How long did it take to see it was about me. My situation.

But what situation?

And I was no bug man. No nature man. No man. Something else apart, solitary, wanting. Though on summer days I had found solace tilling dirt. A thrust of shovel, the affronted squirm of unearthed worms and grubs, a haul of sod, a stir of black gardening soil seeded with wildflowers, perennials, prairie grasses, then rolling out a carpet of mesh fabric to cover in woodchips to transform the front yard into a winding meditation path. I spread the chips with a hoe. Stomped them flat, and then tread light around the path to the mental count of breaths. In, Out. One. In, Out. Two. In, Out. I started over when I lost count, which was often. I felt saturnine and winsome in the wan palette of autumn dusk. In the spring and summer, the first grasses would sprout. Veil my spirals in Pampas Grass and Queen Anne’s Lace, Puff-Balls of Dandelion and crisp eruptions of milk weed pods. Around it piled leaves of something called Honesty Lunaria, translucent like cellophane coins. And Allium, Marshallia, and spiked black burdocks and the busy burrow of ghost moth larvae that feed on their roots.

I spat out a gnat cloud in the prairie grass maze in my front yard and hunched into more bug lore: maybe smell and taste are more dominant senses for Jeremy than sight. Its antennae, like the TV rabbit ears, don’t pick up light but confer another vision, covered in holes like air-cooled machine gun barrels. The holes lead to interior tubes of exquisitely sensitive chemoreceptors. Jeremy sniffs and tastes its way through a Super Baskin Robbins world of 31 thousand flavors. The olfactory data goes straight to the higher brain, packed with memory.

I took another branch off the main path, groping into grass grown thick as theater curtain, visibility zero. What does Jeremy see? According to a Rutgers Science site, the simple eyes see dark and light, and “the horizon.” The compound eyes see movement, and objects in blocky pixels. One writer suggested that Jeremy’s world “is like being trapped in an old video game.”

I had my doubts. Maybe the writer drew too readily from childhood arcades. I spent a lot of time hunting down my son in those places when he was a boy, considering and rejecting one after another child face, written in the flicker of those epilepsy-trigger screens as too blobby, too thin, too dark, too light. And then I would find him, his face of old soul gravity like a Greek bust in a rubble of kitsch.

We always cast the universe as, variously, a clockwork, a computer program, a hologram projection, a TV antenna, bent. A dark arcade, searched.

Gulping more bug facts: flies and other insects may see everything in slow motion (like the scene in the 1960’s Flash comic when Barry Allen sees a waitress’ spilled tray of food suspended in mid-air above him, or Captain Kirk in the episode, “Wink of an Eye,” or Peckinpah bloodbaths, or Keanu Reeves in the Matrix films, or movie car crashes, especially plunges into water). Would this apply to slow-moving insects, like Jeremy?

Slowing everything down so that falling or flying objects—Barry Allen’s spilled tray, Keanu Reeves’ approaching bullets—can be caught, deflected, put back in place. Of course only a “what if.” Not real. Until the wish itself slows down and inhabits every single thing and person of dumb matter that is all the real world has. If you fall, you hit the ground.

Back to Bug Consciousness: the idea is based on the scale of the creature, the relative higher speed of thought processes traversing a tinier form, the greater rapidity of eye movements—saccades—to bring targeted objects into the area of highest focus, the fovea, in a smaller eye. But I thought the speed of thought was a constant thing; would there be that much difference traversing our brain “distances” compared to Jeremy’s nerve connections? Or is it because there are fewer of them than in human brains? And what kind of defense would that be, to see things slow but still move slow, like it does? It sounds maladaptive, to say the least. Subject for more research. Besides, from what I could tell, smell and taste are far more dominant senses for Jeremy than sight. Its antenna, like the TV rabbit ears, don’t pick up light but confer another vision. Jeremy’s antennae are covered in holes leading to interior tubes of exquisitely sensitive chemoreceptors. Billie worked through college at Dairy Queen, so Jeremy may be able to see a fragrant memory of Chocolate Brownie Extreme Blizzard glowing on some molecules of her skin, perhaps a minute downy ambush of lobe and jaw that’s escaped soap and creams, left there when she pushed an errant strand of hair out of her eyes and back behind her ear in the summer of 2015. Which means Jeremy could possess a deeper history of Billie than I will ever know.

I busied myself with excerpts from The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness by Antonio Damasio, and Bright Air, Brilliant Fire by Gerald Edelman.

I wrote to the research:

Damasio and Edelman are especially elegant examples of the trend in consciousness research grounded in neurobiology, and clinical work with brain damaged individuals. Reverse-engineering perception, so to speak, from the baseline of what they call the proto-self, or the primary consciousness of “wakefulness, minimal attention and image-making ability” up through changes into “second-order mapping to the core consciousness of autobiographical memory, extended consciousness, language and creativity.”

The low growl of a jammed machine.

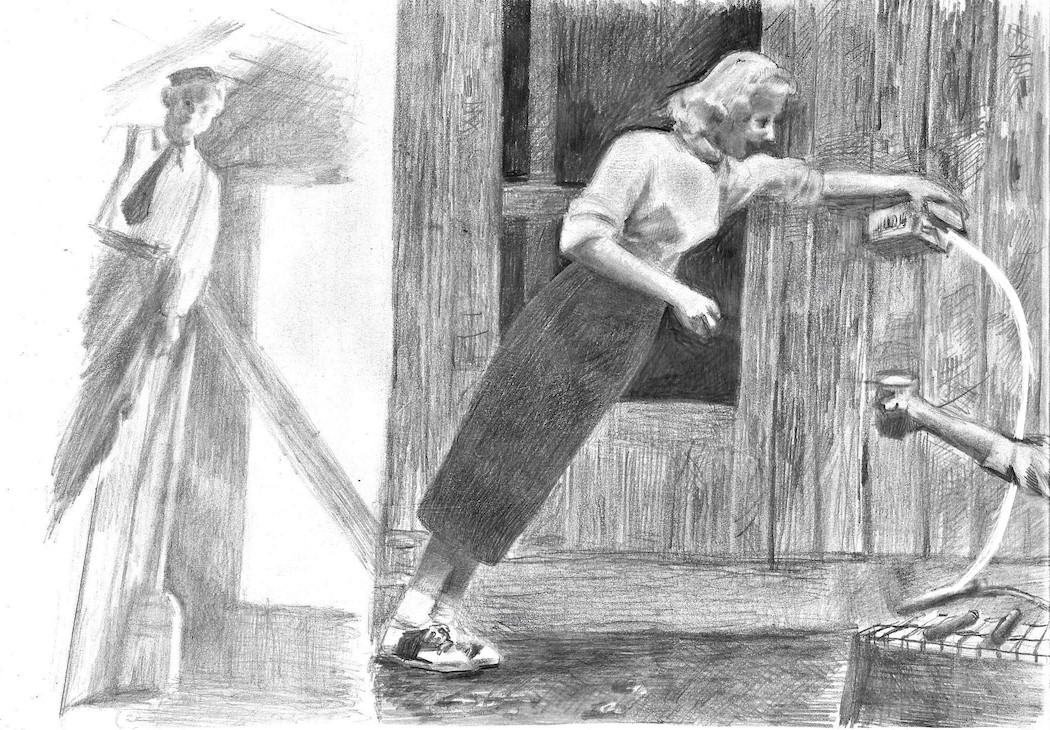

“Tom? Can you fix this?” Billie called me to the big table past our cubicles where she’d been laminating some signs for a training, the source of the hot waxy smell. The machine was a black plastic unit about the size of a two foot 2”X4”. A crumpled corner of plastic stuck out of the roller.

“It looks like a tongue.”

“It’s stuck.”

I was insanely happy she asked me for help. But the plastic cover had to be removed, and the screws were at the bottom of deep access holes that required a very long, thin screwdriver that we didn’t have in the office. I struggled for a while, prying and poking like a Sci-Fi kid avid to reverse engineer. If I could fix this thing. For Billie. She went on to something else. If I could fix it. For Billie. I grabbed a butter knife from the kitchen and thrust underneath and in between the rollers. If I could tug the wedged paper out.

From across the room Billie yelled, “It’s still plugged in!”

Domestic safety 101. Flunked.

Hit something live.

My brain lit up like an old flash bulb.

There was even that WHOOMP sound.

The smell of hot wax, or burning hair? Skin?

All at once it was the winter of the Polar Vortex.

T.S. Eliot, “The Waste Land”:

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or a woman

—But who is that on the other side of you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or a woman

—But who is that on the other side of you?

The lines were stimulated by the account of one of the Antarctic expeditions—I forget which, but I think one of Shackleton’s: it was related that the party of explorers, at the extremity of their strength, had the constant delusion that there was one more member than could actually be counted. Called by some “The third man syndrome.”

If I could get an accurate count. If I could get a fix. Fix the machine. For Billie.

I just stared out the window. All windows. My raw-feeling neural display whenever she emerged over the wall was a blinking and buzzing neon for a Weimar cabaret, or a fly zapper ready to blow.

From Sex on Six Legs by Marlene Zuk:

“Male damselflies have penis equivalents that boast a terrifying array of spikes, scoops, and hooks. The humble chicken flea has genitals bristling with strange knobs, kinks, and coils (praised for) their ‘morphological exuberance’…”

I started over and counted my breaths. The next time Billie talked to me over the wall in her real voice I kept my neural display unimpeachably bland, like non-blinking white Christmas lights or dollar-store Chinese lanterns in the neural patterns of “Friendliness,” “Kindness,” “Benign Indifference,” “Avuncular Harmlessness, “Alcohol-Free Suburban Garden Party of Old People.”

Billie at the wall again. “What are you doing, Tom?”

“I found some more material about consciousness.” Neural display bland as a McDonalds sign.

“What?”

“I’m researching whether bugs have feelings, or not. But that involves consciousness. I don’t know anything about consciousness.”

“Huh.”

Best source yet: Consciousness Demystified by Todd Feinberg and Jon Mallatt. I’d bumped into their article about insect consciousness and was impressed enough to buy their book. Their presentation synthesized what I already had, and expanded it in a more manageable framework. And the comparative drawings of mammal, fish and insect brains were to die for. (Sorry, Jeremy).

Main thesis: we can look at the neural architecture of other animals and make reasonable assumptions about their levels of consciousness, knowing what comparable structures do in the human brain, with human consciousness.

Feinberg and Mallatt hit the ground running with the three overlapping and interactive domains of consciousness: Exteroceptive (stuff from outside of us), Interoceptive (stuff inside of us), and Affective (feeling states about all of it). Like Damasio and Edelman, F and M say consciousness is made out of multi-tiered topographic or isomorphic maps of the three domains in our neural pathways. (Affective consciousness gives a valence or value to places on the maps and is more diffuse phenomena.) These maps inside us are the territory. They are the only world we can know. Kant’s First Critique of Pure Reason: “the world itself” (Noumenal) vs. “the world we experience through our senses” (Phenomenal). But it’s not just our senses. It’s our senses interacting with our neurobiology. The maps are holograms, dynamic in time and affect. A world within.

I stared down at my boots. Shame and scuff. The neurological hologram of boots taking me further in, and the blanched leather friends guiding me on, and out. Would both worlds, like my garden paths, keep crisscrossing into infinity, or would they ever converge into a Real World? The one with all the people I’d known. And lost. Now the boots were crunching over the crisp woodchips of the spiral paths. It was back to summer. The thick prairie grass was shoulder high. My arms breast-stroked through with a loud shush, into a hot dark ahead. Sunflowers bowed. A cricket sprang and a butterfly sat. I stumbled over poplar roots and took a fork in the path. I orbited a spruce sheltering a fat bee over red needles and black pine cones. The path split off again. I entered a tiny sculpture garden housing a fountain cairn of bricks. The holes dribbled sweet-smelling water that ran up the brick and into the air. A wonder spot. A locus of aloneness.

I smelled something hot.

Staring out the window. All windows.

I wanted to tell Billie something, anything, and leaned over the wall, but she raised a finger for me to wait because she was on the phone. I took a break and walked down the block to the free Little Library by the quiet garden in the peach tree orchard. The book I took away was a strange Philip K. Dick novel from 1956 written when he was only twenty-eight, The World Jones Made (half of an Ace Double dos-à-dos with Leigh Brackett’s The Big Jump). Jones features a hand-held device called a “Lethe-Mirror,” an identity/memory-wiping weapon developed by the communists in Korea. It reminded me of a Belgian/Dutch/German movie set in Mongolia, a surreal fusion of semi-documentary and visionary dream adventure called Khadak, from 2006. In the finale, Mongolian herders and an activist theater troop fight back against a ruinous mining operation that’s taking over their land. They immobilize guards with hypnotic mirror crystals, and shut down operations. I turned around and looked at the long table behind my cubicle, where the staff gathered to have lunch or take breaks, but between those times was usually empty. Later in the evening, I could experiment with the microwave, a laptop, a mirror and a bunch of tiny magnets I’d been prying out of the back of refrigerator-attached clips and holders collecting in my drawer. I made a circle of the little magnets on the rotating glass plate of the microwave in a Stonehenge configuration. I propped my cell phone up in the middle with a mirror at its back. Outside the microwave I set up my laptop, and a laser pointer held in place by a clamp attached to the side of the table. The laser pointer had a line of fiber optic cable out the back, running to my laptop. It pointed into the window of the microwave, centered on my cellphone. Opposite the phone and reflected in the mirror was my open laptop. In the center of the screen hung a small box with mirrored sides, held there by a thread attached to the back of the mirror and looped over a little nub of non-permanent gum adhesive on the other side of the laptop lid. The laser pointer fiber-optic cable was patched into a mixer playing a YouTube of Lucretia Dalt’s “Inframince,” the array hooked into a 3-D printer that smelled like hot wax. After chugging and baking for ninety minutes it opened on a black rectangle a little larger than a 2’X4’ block of wood, about two feet long same as the jammed laminator. The face was blank except for a tiny yellow transparent dome, like the bubble window on a level. I switched the YouTube to the 1998 Moon Pix by Cat Power, and the printer set to work on the last components, a hand-grip trigger assembly, and a side-attached butt with intensifier shift that resembled a rotary gear shift on a bike. I scanned and entered one last set of schematics into the printer, and put the fugue gun back into a new mold template I slid into the side. The wax/plastic smell gave way to ozone. I could have sworn vanilla and white chocolate flooded my mouth. Billie’s Dairy Queen. That afternoon I’d stood and leaned over the wall. I had to tell Billie the latest about consciousness. She was on the phone and shushed me with a finger. I retreated. Alone in the office that night I started laughing to myself in the dark, as I had many times and in many different jobs My return at night to deserted work places was a life-long ritual, explained away as “working late” but having nothing to do with the job, unless the job was another labyrinth walk through echoes of voices and laughter, shadows and people held in the air like a memory of an Edward Hopper tableau. Laughing the late capitalism laugh, in the shadow of late capitalism’s maniacal destruction-as-creation stage of late capitalism stage. I touched the gelid window glass and blew on it and felt my eyes blur hot and stinging. I sobbed and slumped over my desk. I sobbed standing, I sobbed walking, up and down the steps, then in circles around the table with the array still chugging out the 3-D model that would blast a hole in this world.

Then the printer finished the final components. I went back to my drawer, gulping tears and snot. Just one last piece. I went back to the drawer for the antennaand put it in the slot. After taking half a Xanax, I taped out a big X on my keyboard, and sent it strobing from my laptop to my cellphone inside the microwave. It was still hooked into the 3-D printer. I went to get Jeremy, long dead now, and wrapped her in a shroud of tinfoil. I put her in the microwave and turned the array back on. I fell asleep on my feet, walking in circles around the table. I inserted the last antenna into a slot on the side of the gun, and it hummed.

Fugue, from the Latin Fuga, related to fugere (to flee), and fugare (to chase). The fugue of music. Polyphonic dance. Bach’s brain.

A joy to be hidden, and disaster not to be found.

The other half of the Xanax.

I inserted the final templates, and more cook time in the printer brought out the “morphological exuberance” of gnarl, knob, hook. My weapon boasted an exuberance of Lethe morphology, a plasma gun capable of inflicting corky wounds and cat face disfigurements in time, and displacement pulses in matter. It was a screamer, a jammer, a buzzer. A bitch. A neural disruptor-imploder of Alzheimer’s Rays, throwing interdimensional purgatory immolation fields in a narrow to wide array.

I saw the other someone on the other side of me, gliding, wrapt in a brown mantle never showing up in the count, screaming, Shoot Tom! Shoot! but under all my gear she sounded underwater. I was wrapped in double thermal eight-in-one gator tubes over my ears and head and back up over my nose, a Velcro rigid face mask on top of that, then ski goggles, thermal watch cap, black leather and fur aviator’s flap cap, (right out of Khadak) hanging loose to keep head swivel free, thermal hoodie, insulated zipper coat, two layers of long underwear under snow pants, two layers of socks, thermal boots, two layers of gloves, scarf to close any gaps. I had just made it to the neighborhood Free Little Library, the same one where I found The World Jones Made, and discovered a biography of Ernest Shakleton. All my expedition gear was interwoven with Faraday-box mesh and magnetic field plates stitched to shield from the blast of the Fugue Gun,, humming to the musical fugue, the neurological fugue, the flight and follow, follow and flight. Damasio makes an interesting distinction between emotion and feeling: “Emotions are the body’s adaptive response to external events or stumuli. Feelings are the subjective experience of them. Various stimuli and drugs can induce the physiological effects and neurological signatures we call Fear, Love, Disgust or Grief without subjects’ reporting any particular feeling states (weirdly, the emotion Lust produces a pattern of neural activity that’s distinct from all other emotional experiences…”). I imagined Billie fixing me with a scalding glare. “That nugget may rankle like a stone in your shoe, hopefully lighting up your brain with the more commonplace neural signatures of Embarrassment, and Shame, ok?...”

Even if we do have a self, all many of us want is to still the music, for a time. Transcend that individual identity, shuck off that convict walk of a mortal coil, to make a new beginning of a pulled-out piece of TV antenna with the glued-on plastic bead. To try and fool my parents and everybody else that I hadn’t gone and broken something in the house, again. That I could save it, fix it, we could fix it, make it new. Trying to quench this thirst for annihilation with the secret machine. Alcohol, sex, love and work wrote the shanties of self before. I lost those full- throated lines. So, I walked the meditation labyrinths. And studied bugs. In silence. Alone.

If I could fix this. For Billie.

Images © Gregg Williard