Part of our uncertainty in Sid’s orientation undoubtedly comes from the expression captured on Sid’s face—it is one of surprise, as though at a sudden

recognition, a bright yet still somehow vacant, even absent look. It is the look on the face of the captured Spaniards of Goya’s The Third of May 1808, looking both out of the corner of their eyes, down at their fallen comrades, and also straight ahead, down the barrels of the French. Perhaps also the look that we have when first encountering Goya’s painting. Sid’s shock, though, must come from the prescience of a different kind of shot than Goya’s Spaniards anticipate: the camera’s flash, stopping him at the door of the cab just when he should be closing that door, safely on one side or the other. Perhaps, rather than the flash of the camera, the shocked look on his face comes from a flash of something that his eye catches farther down the street while accommodating his frame to the cab’s. Or a memory.

Naturally, one finds oneself searching the photograph for any traces, any clues, that might suggest themselves as the object of Sid’s attention. There is the suggestion of a hand in the cab’s back seat, on the side opposite Sid, the street side, but it is only a suggestion: it may simply be an imperfection of the print, or a brief refraction of light inside the cab caught by the exposure. The hand seems visible only at the very edges of our visual field, where the eye is normally sensitive only to motion; when looked at directly, the suggestion of the hand simply evaporates into shadow. It is the hand of another of Goya’s paintings, The Fates, the hand or hands of the mysterious fourth figure, the

woman who sits between Lachesis, with her magnifying glass, and Atropos, with her scissors. As with the Goya, we search in vain for the hand in our photograph to explain the meaning of this figure and of the scene.

If we instead turn our attention to the direction of Sid’s turning face, following its gaze left from the cab and up the empty street past the Chelsea, we find other objects worthy of inquiry. Though there are no other figures on the sidewalk or the street, the photographer has managed to capture a man coming up out of a well below the street on the left side of the hotel’s awning, and a face in the window to the left of that well. Perhaps it is to one of them that Sid is turning his attention at the moment of the exposure.

The cab that Sid is entering or exiting has pulled up short of the awning, and so the cellarway that brackets the picture’s foreground might well seem to be the object of Sid’s attention. Because the photo looks to have been taken from the second floor of the building across the way, it is possible for us to see what Sid may be looking at, indeed, to see more than would have been possible for Sid, there at street-level, to see. Emerging from the doorway at the bottom of the stairs in the cellarway is the man’s double, a second Sid Vicious only feet away from the first, turned in much the same tortured position, and with the same surprised look on his face.

Once we have recovered from our own sense of shock at the novelty of finding a second Sid in the frame, in what seems to be the same position as the first, even wearing the same expression, we naturally begin to look for other correspondences between the two men, the two Sids. In our examination of the cellar doorway in the photograph, we experience a kind of mirroring, or doubling—not only of Sid, of an expression on his face, an orientation of his body, but also, possibly, of an object and its relation to Sid in space—a hand, emerging from or retreating into the dark cellar. This time, though, the shape is so clear that, although the light of the cellar doorway is inadequate to easily apprehend the nature of that shape, still, the shape itself is readily apparent. Which is to say that, even if we cannot be sure that it is a hand or a trick of the light, or yet another defect in the print, whatever it is, it is certainly hand-shaped. Sid seems to be ascending the cellarway’s stairs, and the torque of his

shoulders caught by the camera’s exposure gives him the look of Michelangelo’s Sistine Adam at the creation of Eve, with the shadowy hand occupying the same spatial relationship that Eve does in Michelangelo’s fresco, as though it were springing to life out of Sid’s twisting side.

This second Sid’s attention, if we continue the line of his gaze, and, by extension, then, that of his street-level counterpart, is directed out of the frame, to the left. The unsolved murder of Nancy Spungen, and the curiosity-seekers that held séances there after her death, eventually prompted the Chelsea’s management to remodel the first floor so that the room that Sid and Nancy stayed in, room 100, was subsumed into its several adjacent rooms. But it is precisely at the left edge of the frame that room 100 would have been at the time this photograph was taken and just there, at the edge of the frame, is yet another, a third Sid Vicious.

This Sid’s head hangs in a window, once again wearing the same expression and twisted in the same attitude, with the same orientation—off to the left: in his case, clearly out of frame. Because of the glass, this third Sid’s face is further blurred and streaked, calling to mind the longitudinal distortions

of Maffei’s Perseus slaying the Medusa. This Sid is either turning back in to the room, looking back at something that cannot be guessed at on our side of the glass, or away from it, out onto the street, beyond the edge of the photograph. The medium itself has done the Gorgon’s work for her—Sid is stilled, in perfect stasis between living and dead. Mercifully, then, for us, the object of this last gaze is obscured—made invisible by the framing of the photograph and the circumstances of its capture.

In following this chain of Sids, we find that the composition of the photograph, on an upward diagonal slant as we move from right to left—which is to say, against the Western tradition of reading things left-to-right (in that tradition, then, and against the direction of Sid’s gaze, right-to-left, we would travel instead down, diagonally, as though down a slope or a staircase)—actually distorts the meaning and direction of that gaze. For, if we look more closely at the gaze in the frame of the photograph, we find that the first Sid, the Sid that is entering or exiting the cab, must in fact be looking past the second Sid at the bottom of the cellarway to the third Sid hanging in the window. If the first Sid were actually looking where the composition wants us to believe he is looking, at the Sid at the bottom of the cellarway, we would see even less of his face than we do, because it would be pointed down at the street’s surface and away from the photographer across the street. This seems then not simply a relay of gazes, traveling in a straight line, but rather a triangle, in which the rightmost and center points converge on the leftmost point, as hypotenuse and cathetus converge.

The Sid at the cab must then be looking in the direction of the Sid at the window, either taking him in or sharing in the object of his gaze. And yet, it is barely possible that he also catches the Sid at the cellarway door at the very limit of his peripheral vision. The only plane that Sid’s gaze could not break in this moment or the next is that that exists behind him, out of frame, and it is through this realization that we see that this Sid is less Goya’s Spaniard, his back against a rock, than Rubens’s Orpheus, looking anywhere but where he must not look, behind, and yet very conscious of that forbidden space, if only as an impossibility.

Again, because of the three-quarters view we are given of the second Sid’s face at the cellar door, and the angle of that face in the photograph, we cannot believe that he is looking up to the third Sid, nor back at the first (as with the first Sid, and, in fact, the third Sid, the direction of his gaze makes this impossible anyway). He must either be looking at something hidden by the lip of the sidewalk and the angle of the photo, or turning back to look in at the doorway.

It seems evident, then, that we are not meant to look out of the frame to the left, as the Sid at the window is doing and as we would be led to do if this were simply a relay of gazes. And like the first Sid, we are prevented by our own orientation, dictated in our case by that of the line of the gazes in the photograph, from traveling in the opposite direction, to the right and also out of the frame. Instead, though the Sid at the cab may indeed be sharing in the view of the Sid at the window, neither one is capable of sharing whatever view the Sid at the cellar doorway must have, and, as a result, the Sid at the cellar doorway cannot in any meaningful way “pass on” his gaze to the Sid at the window. A line connecting these Sids cannot represent anything other than wishful thinking on our part.

But if the Sid in the cellarway cannot share in the gaze of his two above-ground counterparts, then even the triangle disintegrates. And yet, the fact of the absolute similarity in their expressions and orientations tells us there is something of significance there. What must then become clear is that this photograph intends to capture not the moment of these gazes, which gazes in any case cannot be unified, but either indicate their cause or lead us to speculate on their aftereffect.

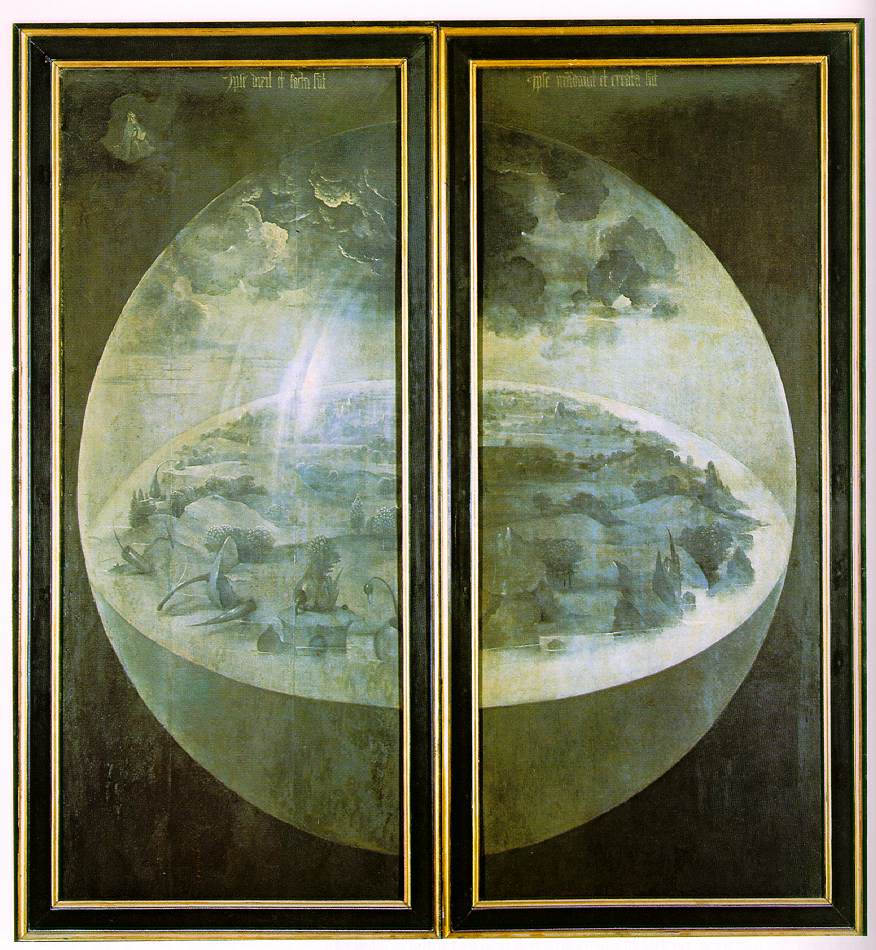

Might we then posit that, whatever the direction or object of each Sid’s gaze at the moment of the exposure, all are caused by the same impetus? The photographer—or, at the very least, the photograph—wants us to think so. The perfect line of their gazes, the similarity in both facial expression and torque of physique, even the slight tilting of the camera, all lead us to believe in some specific and shared cause, durative and therefore insusceptible to capture in a static medium like photography. In fact, it is precisely this feeling, that there is something “missing” in our understanding of the moment, something on either side of it, as Lachesis and Atropos on either side of the mysterious figure in Goya, or perhaps, in a sense, more literally, the Shutters of Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights, that leads us to assign meaning where there is none—that is, to the direction and object of the gazes—

where, we have seen, it is impossible to derive a singular meaning in this particular moment, because this single moment is inadequate to link all three. Nevertheless, we seem to always come back to that obscured figure whose hand we see in the cab and in the doorway, and whose existence we posit as a matter of symmetry, in the window.

We may recenter ourselves with respect to the photograph, as though taking hold of the Shutters and literally unfolding Bosch’s masterwork, by examining each instance of that unseen figure—or perhaps, more to the point, the degree of its obscurity— in the light of the others, and hope thereby to understand the intention of the photograph, separating it, too, into a kind of triptych. The composition again seeks to distract us by drawing our attention along the direction of the gazes: even with our new understanding, if we persist in following them from right-to-left, we cannot make compositional sense of the sequence.

True, in the first two instances, it seems that we are following some sort of apparition-in-process. The blurred “hand” in the dark of the cab comes clear in the light of the doorway. But in the third part of this sequence our design is frustrated, because Sid is alone: the hand—or rather, the body attached to it—that we expected to appear more fully has instead completely disappeared. We might suppose, based on our earlier (as it turned out, false) hypothesis, that we are being asked to look beyond the frame at what was emerging from the shadows in the first two parts, what we supposed was occupying the attention of the three Sids. Perhaps the hand and the body it belongs to are there, but just beyond the frame, out on the street, or in the next window. But this ruins the very thing that convinces us that there is a progression here—the sense that, even though they are separated by space, each Sid occupies exactly the same relation to the apparition as the other two, for if it is truly beyond the edge of the frame, this third Sid has been reversed, with his apparition appearing on his right side rather than his left. It seems that, if we are focused purely on what is in the frame, we can find no real correspondence in any linear fashion, even in this now discontinuous sequence.

Moving right-to-left evidently presents a problem no matter how it is approached, whether as relay, triangle, or triptych: it is equally problematic moving in the opposite direction, going from nothing, to the most clear apparition, to the blurred apparition of the cab. The only way that it can possibly make sense is to travel from the left border, where Sid at the window is alone, to the right border, where Sid in the cab might be accompanied by an unseen person—one who is speeding away—to the center of the photograph, where Sid stands in the doorway with the disembodied hand beyond. This suggests a progression much more like a spiral than a line or a triangle. It suggests that we are being drawn into, not out of, or away from, the photograph.

And, as we begin to consider this, we discover that the Sid at the center of the photograph may be slightly displaced after all, with the doorway, and its hand, at the true center. This shifting center depends on whether we right the photograph’s slight tilt or leave it as it is.

Too, the cellar being the lowest point, it is only natural that things would spiral in, and thus down, into its center, into the “drain” as it were, of the composition, its lowest point as well as its deepest, in terms of focus and depth of field.

Consider that, in each instance of his appearance, Sid’s attention is being distracted not by something happening strictly out of the frame, which, again, the line of that gaze wants us to believe, but by something which is in the frame but still invisible to the photographer. In the case of the first Sid, at the bottom-right, we may conclude that, wherever his gaze is directed at the moment of the exposure, he is likely being distracted by something in the cab, and thus something made invisible by the cab’s opaque surface. In the third instance, Sid at the middle-left, in the window, he is, it seems, being distracted by someone or something in the room, something, then, eclipsed by the wall of the hotel.

In the light of this multiplied distraction, it becomes clear what had first puzzled us about the precise direction of Sid’s look of surprise, and the artifice of the photograph’s design—in the moment of being surprised, the eyes seek for the source of the alarm—they can have no fixed or preconceived goal. In other words, Sid cannot possibly know where to look in this instant—if he did, he would not be surprised. The direction of that gaze in the instant is irrelevant; the fact of the surprise is all that is relevant. If someone in this room suddenly disappeared through the floorboards, and we registered her disappearance but not the point of her egress, we too would be left searching in precisely this way—without aim, our frantic gazes never resting on any particular object.

And so our supposition that the second Sid, the one in the center of the photograph, is turning back to the doorway, and that that doorway offers the center not only of the photograph, but of the scene itself, of the spiral that the scene is leading us down into, is confirmed by our sense that the twisted posture that this Sid, too, is caught in, indicates that he is being disturbed by something that is not so much out of the frame as beyond the photograph’s surface—in this case, in the darkened cellar beyond the lighted doorway. As in the other two instances (the possible occupant of the cab and the events in the hotel room), what we are considering is someone or something that, strictly and spatially speaking, is in the frame, that could be shown, but is nonetheless obscured.

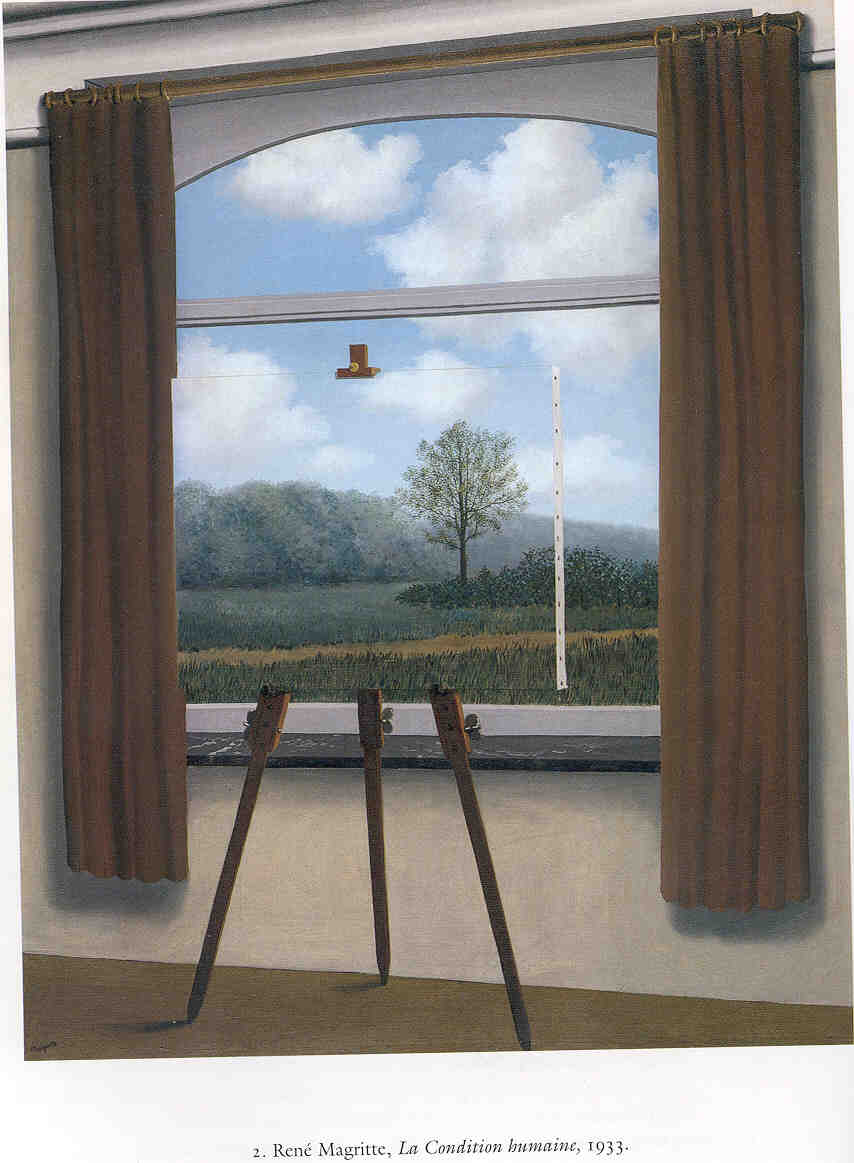

Our reaction, then, is the same reaction that we might have to Magritte’s La Condition Humaine: as spectators, the object of our gaze disappears beyond what we see into what we know or believe lies just behind the painting in the painting. The only way to make sense of what we are presented with is to see what is on the other side of it, something that is denied us. It is just beyond the reach of the eyes; in the case of our photograph, even of the photographer’s instrument, impossible to realize because of the solidity and opacity of surfaces, the very nature of light and its refraction.

By emphasizing, through this precise, careful framing of the Sids’ gazes in the moment of exposure, an object that is just beyond the powers of photography to reveal, and thus, just beyond the powers of human perception—that is, vision—to reveal, the photographer calls our attention to it, past the Sids. We are not so much invited to contemplate the photograph as to what lays (literally) beyond it, on the other side of it, the site of Sid’s lost look.

In our three-dimensional world, in the world where we can open the shutters to reveal the triptych or push aside the painting that sits in front of the window, we pick the photograph up and turn it over, looking for the object denied us and expecting against all odds a solution, but find instead only the white expanse of the contact paper. What is just beyond the photo, this blank expanse, overtakes the image in our mind, interrupts the line of our original gaze and replaces its object with a new object, a further examination, this one seemingly of nothing at all, promising nothing to us. As with Magritte’s painting, we will never be able to find a way beyond our photograph, never be able to penetrate its surface; we cannot be sure that there is anything more than nothing waiting there for us. It is an impossible, an untenable, position, precisely because it is so frustrating, a position which we must nonetheless accept. It is this frustration, a mimicry of the very act of perception, of seeing separate from even the possibility of understanding, of “grasping” anything beyond the surface, that both excites our imagination and leaves us haunted, possessed of a feeling of loss that cannot be put right.