Suspension

My mother lived in a mason jar. Twice daily, I took the lid off. She said it was to allow her to breathe, but she only seemed to dive deeper.

Precarious Advances in the Field of Biological Sciences

A theory existed, saying that her bones had one day become gelatinous, and she had slipped into a jam jar—an expedient off-handed solution orchestrated to prevent herself from sliding away into the cracks between the walls and the grasses. Once in, it was too late. She could not possibly convey instructions for future decanting.

According to this theory, she had for many long and industrious years sought to understand the secret language of slugs. From within her internationally renowned laboratory she had lured and cajoled the creatures up from their mouldering depths through extortions, incantations, and promises tempting to a gastropod mollusk. Once captured, she attempted to penetrate their enigmas.

Ruthless, extraordinary, and infamous, her research nonetheless remains unknown: she had always eschewed assistants, and her lab notebooks vanished, or were destroyed.

Several Types of Bodies Commonly Found in Suspensions

On the solstice and the equinox, I would take her to the lake. She was prone to desiccation, and these quarterly pilgrimages proved invaluable. I would unscrew the lid, and pour her into a butterfly net, and plunge her into the cool still waters. The waters seemed black at first glance from the surface, but down below they were a bitter walnut yellow. The tincture stained her skin green and lurid for the first few years, but afterwards it added a peculiar Sephardic luminosity to her flesh. As if she were lit from within with the born or dying sun she’d fled her jar to worship.

My Mother at Winter Solstice

During the winter solstice, I would have to bring a pickaxe and use it to break through the crust of ice formed on the lake. As I held her beneath the surface the handle of the butterfly net would form complex crystals of frost. Delicate, as though it was trying to tell me something in a code of its own sharp language. My mittens would leave a pelt of wool along its surface, softening it. Each winter I worried that my mother, too, would freeze, and not fit back into the jar after I pulled her out. But this never happened.

The Preservation of Traditionally Edible Plants

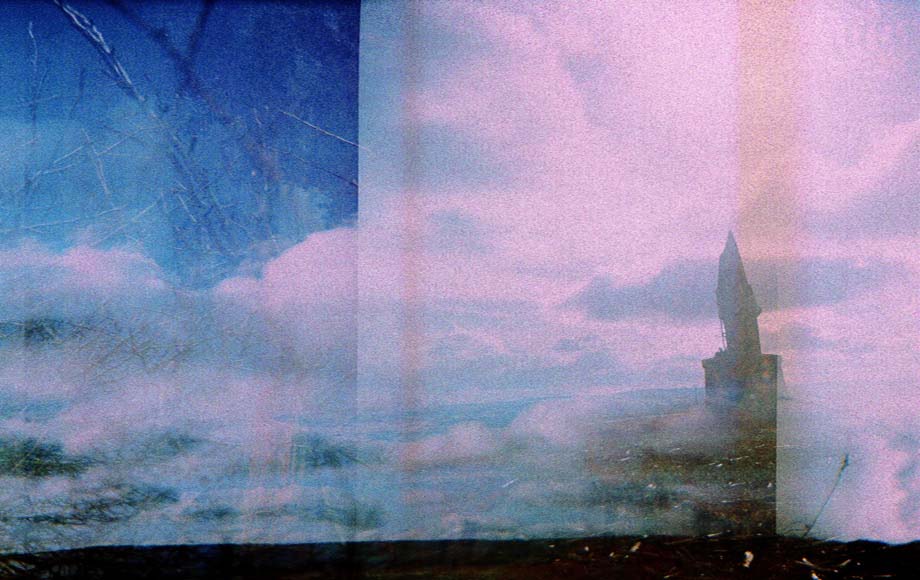

According to one legend, a mysterious Hungarian hurdy-gurdy man—no poor busker, he—had arrived in the town of my mother when she was a young woman. This Hungarian materialized in her meadow as though from nowhen and nowhere, as though conjured from an errant wormhole, dislocated from the familiar continuum of time and space. And through the Pythagorean drone of his soundboard, certain bystanders distinctly heard him offer my mother a sizeable, oddly luminous glass jar of watermelon pickles.

The rind was striped a violent chartreuse and emerald, with a shock of opalescent white, and then a thin grin of pink. Alluring.

She took the jar from him for the price of an irresistible kiss, and when she reached in her sweet fingertip, her world inverted.

In her place on the meadow were sixteen slices of preserved watermelon, sliced and saturated with vinegar, dark sugar, black pepper, and vodka.

In their place: my mother.

My Mother at Vernal Equinox

At the spring equinox, I know she enjoyed the baby minnows. Their small, even bodies existing as perilously as slivers of dream, half-silvered in the dim gloom of our lagoon. I would hear a faint cadence, like laughter, from the water, and many of the small new ripples in the lake were caused, I suspect, from her attempts to catch them in her hands, or possibly her mouth. They must have been fascinated by her teeth, if she had any. By her lack of animosity.

Each year it seemed there were more of them, as though they waited for her. As though it was also some sort of holiday in their society, or perhaps some call to tzedakah. Thousands of them swam in and out of the holes in the butterfly net, it having been designed to catch things with wings, not fins.

Even through the distortion of several feet of water, I could see how they longed to touch her, their scales brushing up delicately against her flesh. Everything starting to thaw, beginning to warm.

What Once Began as Grains of Sand

In my childhood, once I taught myself to read the Yiddish of my purported ancestors, I came across tales that said my mother had been an extraordinary circus performer—a goyisha contortionist who had fallen in love with a Ukrainian glassblower, fresh from the shtetl.

A collaboration, a labor of love.

The rest was mystery, and artifact.

Often Mistaken for a Bird by the Ignorant or Unknowing

When we went out together, I would cover her jar with an embroidered cloth. Along the street, people mistook it for what is often used to shutter a birdcage and prevent the creature from singing.

Others said it was some kind of schmata or sheitel or tichel, peculiarly covering her jar and not her head.

Or a meil, but covering a woman instead of the Torah.

They looked at us askance, unsure of whether to praise or to condemn, and uncharacteristically afraid to ask.

Her unspoken demand for this covering made me uncomfortable. She would not answer my questions about whether she was ashamed, or secretive, or perhaps merely reclusive.

They are very different sentiments and it bothered me, this ignorance about exactly which impulse I was asked to enable.

My mother’s hair was a gorgeous bright red—vermillion, even—and formed a root-like webbing in several places. After a few years, it grew to a sufficient length and thickness that allowed her a more dendritic concealment of her form.

A Simple Situation Privileging the Innate Capacity for Synesthesia

When I was sixteen, she developed tentacles. They were retractable.

This occurred during the period in which I began excavating the garden shed. I found a brief compendium of well-preserved old seventeenth-century music manuals dictated by a blind limyk and covered in an intricate Byzantine lacework of slug slime.

How had they come to rest within our garden shed?

This nonetheless stimulated my considerable interest in the lute. After several days, I was inexplicably proficient.

It was during the times I played that her tentacles extended nearly their full length. Once in contact with the surface of the glass, they would curl into spiraling tendrils, like fern fronds. Constant movement. Grace. This is how I learned that music creates light and scent that is imperceptible to traditional human sense organs.

Two Substances Whose Manufacture Frequently Necessitates the Use of Cellulose Acetate, Hydrolyzed Collagen, and Ammonium Chloride

When we went to the movies, we smuggled in several long strings of black licorice—they were sold to us by the Dutch children every autumn, who knew to offer us only their very best. I would lower the strands into her jar gradually through a small hole we used for this and similar purposes. I would hold the spool of licorice in my lap and let it slowly spin out through my right hand, feeling the hollow weight of it between my fingers as I turned the remainder of my attention to the film unfolding on the screen.

Over time, the string of licorice would unroll from its wheel, sliding through my fingers in quite the same way as the strip of film slipped from its reels through the projector.

We would spend hours like this in the dark—me consuming the story, my mother lovingly macerating the flavorful candy.

Treasured closely by Alexander the Great, licorice is actually a fertility-inducing legume.

Ah, cinema.

Heavy Rainstorms

Another source of happiness for my mother was heavy rainstorms, but only when experienced from within the house. When I was younger, I thought she favored the cataclysmic rush of humidity and moisture, or that perhaps she experienced a bittersweet nostalgic longing to feel the pelt of droplets against her subtle flesh. I fleetingly hypothesized that she fancied the thunder, with its astounding lack of chromatic scale.

As I became older, I realized her deep kinship with the windowpanes. Their translucence, their transparency against air and water, their mineral urge to separate and define.

My Mother at Summer Solstice

While summer solstice marks the day of greatest light, it comes early in the season, perversely preceding the days of greatest heat. Imagine if they both occurred at once. Imagine the levels of stimulation that would likely bring us to our own destruction.

We appreciated the ebullient young leaves, still emboldened by May’s blossoms, as yet magnificent in the froth of arboreal mating rituals involving pollen, pistil, stamen, and bloom. The air at dusk actually whitening, as if with milk.

The bisonoric bellows of the bullfrog in his reeds.

The One Who Blushes

One morning I awoke to find letters etched on the surface of my mother’s jar: םיראמ: the one who blushes.

Who is this woman?

And why have I come to believe that she is my mother? Perhaps she is some god, and I her sibyl.

By sunset, the word had vanished.

Her Portrait in Codex

For as long as my conscious memory can recall, I have carried and cared for this mason jar, for this woman inside the mason jar, for this being, my mother. I know the concertina folds of her fingers pressed against the glass, the arterial delta of her wrists. The alarming perpendicularity of her knees and nose and thumbs. The stitching of her spine articulated within liquid.

I have fully accepted the nature of her existence from the outset, or so I believe.

Is she trapped? I may as well ask the blackberries in their pot of jam.

To all who understand the significance of her jar, she is absolutely caught in allusion to a fetus. Was I once similarly inside her?

What is she waiting to become? And how can I best help bring that to its fruition?

Or is hers a perpetual becoming, with no final moment of birth? She the queen of the liminal.

My Mother at Autumnal Equinox

Cats have followed us down to the lake this year. They were the kittens of the spring, and theirs are the mice whose fur is the color of dried leaves, of stones upturned in a field following the harvest. Her heartbeat swells and changes the pressure in the mason jar—the tin button on the lid plunges down, and then pops up, then down again.

My mother is the source of other legends that are concealed within the kind of arcanery that allows for few new pupils—clearly, these texts suggest she is an augur.

And apparently ancient.

According to them, she is directing the birds, the fishes, the snails. She is advocating for the perpetual return of the comets, whose tails she commands with genius precision. Because of her, the absolute fecundity of a supernova.

When I plunge her briefly into the chilling waters of the lake, I finally understand. That which is most powerful must most comprehensively be contained. For an example, consider the word: without its form, our utterances would be screams.

Amniote

Today I crack the eggs for a quiche and I think she looks at me, quizzically, as I strike each shell against the old tile countertop. It fractures, and for a moment I believe I hear a gasp. The shells lie bereft in the palm of my hand. Purposeless only because reduced of purpose, yet somehow elevated through its sudden pointlessness, through a charming inutility—the uselessness of an empty eggshell—its cracks revealing a truly glorious apparatus of calcium and chemistry.

Here in my hand rests a futuristic cathedral. Anatomical geometry that startles. A mineral womb bleached the color of bone and chalk and eyeball. The yolk as surprising as marrow, that something so soft and liquid, etcetera.

The shell in my hand somehow midwifed, as though delivered of that sweet parasite life, the zygote yolk and its mucus.

A Russian doll birth—a chicken purging the egg, and then the egg purging the yolk. Eventually the intestine and then anus purging the yolk, which is then purged by the pipes and then the sewer.

Sympathy for each unlikely oviduct. Each triumphant in their masterful final achievement: emptiness.

Just when I have tormented myself—wondering if my mother thinks me a murderer, if she imagines my hands on her jar at some future date, similarly splitting it, pouring her out into a drain or a piecrust—after believing nothing escapes the notice of my mother’s highly perceptive intuition for metaphor and suggestion, I see that from her position in front of the kitchen window she is twisting and arranging her appendages within the jar to create shadow puppets, life in light against the white face of the oven. A camel. A monkey tree. A quail.